So I Finished the Main Story of Dawntrail, and...

What's good, bad, and ugly about the latest expansion of the story heavy MMORPG. Strap in, it's gonna be a long ride.

Obligatory major spoiler warning. Seriously, if you haven’t finished Dawntrail’s main story quest and don’t want it spoiled, DON’T READ THIS YET.

Some among my readership might be wondering why it is that I keep coming back to write about Dawntrail lately. Okay, perhaps saying I keep coming back to it isn’t quite right, since I’ve only written about this specific expansion twice, and the first time I wrote about it was at the end of January, some five months before its release. Nevertheless, the engagement with the prior three articles I wrote on Final Fantasy XIV shows that they’re not exactly major attention grabbers, so why keep writing about it?

To be frank, my reasons are more self serving than anything, and hopefully those of you who choose to read this first impressions review of my experience playing Dawntrail will see why. You see, Dawntrail finds itself in a very unique place where FFXIV expansions are concerned. As I’ve mentioned in my prior essays on the expansion, Dawntrail sits in a strange and uncomfortable spot compared to its four major predecessors. Endwalker, the previous expansion which was released at the tail end of 2021, saw the completion of the game’s decade long overarching plot in a manner that, for the most part, was very well received. It wasn’t perfect by any stretch, but the main story quest satisfied most of the player base by providing a story that was not only compelling, but emotionally resonant. Add to this the fact that it further expanded on the lore of the game’s now massive world in a manner that was not only internally consistent, (for the most part) but thematically as well, and it becomes quite easy to see why Endwalker’s story is considered to be a success, even when its shortcomings are taken into account.

Considering what came before, Dawntrail was left with a daunting task before it. Not only does it follow on the heels of what’s considered to be one of the strongest expansions in the game from a narrative standpoint, it’s also meant to act as the jumping off point for future stories within the game. To paraphrase the game’s director Naoki Yoshida, lovingly known by the community as Yoshi-P, Dawntrail will help them setup the next decade of stories his team wants to tell with this game. That’s a lot of weight being carried on the shoulders of this expansion, and with that weight comes a great deal of uncertainty. Does Dawntrail have what it takes to be the pathfinder that leads us to the next decade of great stories told within this world, or is the weight it’s made to carry too much for its shoulders to bear?

From my experience, the answer is a bit of both. We’ll have to see where the endgame story content takes us over the next couple of years to know for certain how successful the expansion as a whole will be; see what sort of threads they lay down for us to potentially follow. When it comes to the events that take place in the city of Tuliyollal and the greater continent of Tural, though, it’s a decidedly mixed affair for a number of reasons.

A Tarnished Rite of Passage

When it comes to critique, I prefer to start off with the positives before I start digging into my criticisms. I touched on a specific positive aspect of Dawntrail already in my last article on the expansion, Revered King, Virtuous Father, in which I explored the positive characterization of Tuliyollal’s founding ruler, Gulool Ja Ja. Through him, we learn a good amount of the most interesting aspects of Tuliyollal as a nation, including that it’s considerably younger than we might’ve expected, given the Final Fantasy franchise’s penchant for presenting us with ancient civilizations. Gulool Ja Ja is also the character who sets up the primary story of the expansion’s first half, that being the Rite of Ascension. To briefly recap what I discussed in the prior article, Gulool Ja Ja has been ruling over Tuliyollal for about eighty years. He’s an old man by this point, and as powerful and lively as he still is, he recognizes that his days are numbered and he needs to pass rule on to someone else. Thus, with some help from the leaders of the various communities and tribes that exist under his rule across Tural, he gathers up four potential claimants to the throne and challenges them to not only complete seven tasks set out by his chosen electors, but to then find the fabled City of Gold, which he discovered during his own journeys across the continent in his youth.

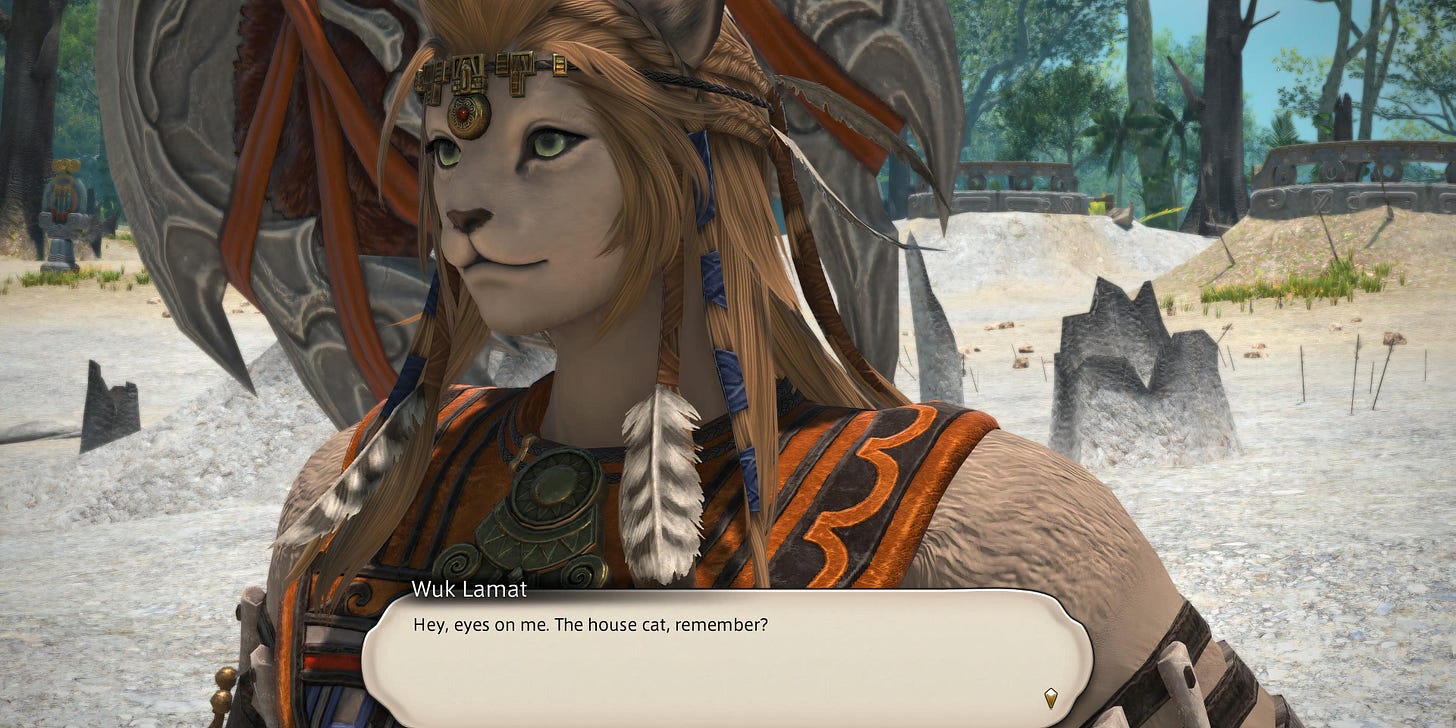

The claimants chosen are his three children; his natural born son, Zoraal Ja, who is the captain of his nation’s guard; his adopted son, Koana, a scholarly type who studied with the Sharlayans, whom we spend much time with in Endwalker; and his adopted daughter, Wuk Lamat, who wishes to know her people better and seeks to maintain the peace her father established. There’s also one other from the general populous who won the right to act as a claimant by winning a tournament in which the strongest and most capable citizens would compete for the opportunity to take part in the Rite, Bakool Ja Ja, who effectively acts as a bitter rival to Wuk Lamat and presents an inverse to the values of Gulool Ja Ja.

As I mentioned in the prior article, it’s Wuk Lamat we player characters assist in the Rite of Ascension. During the final patch of Endwalker, which exists to setup story of the following expansion as has been the tradition since Heavensward was released over a decade ago, Wuk Lamat comes to Old Sharlayan to meet with her old friend Erenville in hopes of recruiting worthwhile allies to assist her in her claim to the throne. After joining her on a short adventure, we come to see that Wuk Lamat’s got a lot of gumption, but also a hell of a lot left to learn, and who better to learn from than the Warrior of Light, the hero who’s saved the world many times over?

This through-line is meant to be carried throughout the first half of Dawntrail’s story. Our journey with Wuk Lamat is set up as one of mentorship to a promising but ultimately unprepared young woman with aspirations of honoring her father’s good deeds. It’s a strong premise with the potential to become engaging on the occasions the story allows for it to be thoroughly explored. Unfortunately, those moments don’t come nearly as often as I’d have liked or as they need to in order for Wuk Lamat’s character to feel properly realized, which she needs to be, lest she squander the spotlight position she’s taking. Keep this in mind, we’ll be getting to it later.

Across the course of the Rite and the seven Feats needed to complete it, we’re given the opportunity to learn about the various cultures that make up Yok Tural, the southern half of the continent. From the Hanu Hanu, large bird-like creatures with colorful plumage reminiscent of tropical parrots, to the diminutive traders and llama breeders of the Pelupelu, we traverse the Amazon inspired jungle of Kozama’uka and the cold and arid mountains of Urqopacha with our party in tow as we try to get to know the cultures of these people via our completion of their Feats.

I won’t pretend as if the story is gripping here, which isn’t something I wanted to say. The rites of the Hanu Hanu and the Pelupelu, which can be played in whatever order we choose, effectively make up the first two chapters of this half of the story. They are our proper starting points, our introductions to this new land outside the walls of Tuliyollal. A land which is meant to be a nation that shares this city’s name. Alas, as we deal with both the Hanu Hanu and Pelupelu, as well as the remaining five cultures we encounter moving forward, we quickly run into a problem: it doesn’t feel like we’re dealing with a singular nation at all, because these aren’t a singular peoples. Each of these tribes feels completely separated from the rest, and no real effort is put into making it believable that they’ve come together as a unified nation. Instead, they feel much more like disparate cultures who came together under a political alliance, with the only indications of unity being Tuliyollal itself, and even then only because we see people of Tural’s various races intermingling and living alongside one another. We rarely see this anywhere outside of the city, with the exception being the far more typical humanoid races that we already recognize from the base game and its earlier expansions. Indeed, it quickly detracts from the idea that we’re attempting to foster understanding of the needs of a nation when none of its supposed citizens seem to share anything in the way of a national identity. The Pelupelu are particularly egregious in this considering they’re supposed to be the major traders and money men of this land, yet we never actively see them engaging in commerce with other peoples.

What this feeling of tribal disparity doesn’t detract from is the beauty of the zones their stories take place in, one of the wins Dawntrail gets to carry on its belt. Dawntrail brought with it the first major graphical update in FFXIV’s history, a near complete overhaul that not only leads to the regions we explore in Tural looking absolutely stunning, but the older regions in the game as well. Everything from improved character models to better textures on environmental assets to a sizable overhaul to the game’s lighting systems has lead to FFXIV looking better than it ever has before, and the six new zones in Dawntrail are proud to show these improvements off. Kozama’uka’s jungle is especially good looking, as is the haunting and ethereal blue forest in the second half of Yak T’el, the game’s third region. My personal favorites, though, have to be the fourth and fifth regions, Shaaloani and Heritage Found respectively. Heritage Found features some of the heavier sci-fantasy elements that FFXIV has since become known for over the years, presenting us with a perpetually stormy region that marries the feelings of a hedonistic high-tech society with an Wild West styled post apocalypse.

Shaaloani, on the other hand, proudly wears its Western influences on its sleeve, to the point that I’ve actively seen players refer to it as Final Fantasy Texas. Indeed, my immediate reaction to my friends as I played through that zone was that it felt like I was playing a miniaturized Final Fantasy version of Red Dead Redemption. From townships that sprout up around a trading post or railroad, to abandoned mining facilities inhabited by bandits, to a fuel extracting operation reminiscent of the oil boom settlements shown to us in films like There Will Be Blood, and finally, a camp of natives posted near a forest lake, Shaaloani’s about as Western as Final Fantasy can get. It hearkens back to the days of Bonanza and John Wayne movies, and to the Spaghetti Westerns popularized in the 60’s. There’s even a little Harryhausen love in there, as this arid plain is also home to fucking dinosaurs! That’s right, we’ve got a little callback to the Western monster movie, The Valley of Gwangi, with the herds of triceratops and the flocks of pterodactyls that roam certain areas in Shaaloani. The music only serves to further this, too, made to be reminiscent of that particular style of electric guitar common in Western movies. In case you couldn’t already tell, I loved playing through Shaaloani, especially since it acted as a welcome break from the Rite of Ascension that comprises the first half of Dawntrail’s story, and the heavier second half.

We’ll get to that second half soon. Before that, I need to touch on the two strongest segments of the Rite of Succession story - that being the second half of Urqopacha, and the second half of Yak T’el. In all, we encounter six different peoples across our journey through Yok Tural. The Hanu Hanu and the Pelupelu I’ve already mentioned, but we also have an encounter with the moblins, who are quite literally the base game’s goblins with different colored outfits and rebreather masks. They make for an mildly entertaining call back to the Heavensward expansion, but beyond that, I didn’t find them particularly interesting. Where the story really picks up steam is after we finish our work with them to make for the upper reaches of Urqopacha, where we meet with what remains of the Yok Huy, or the giants.

This was the point at which the Rite of Succession story finally started to grip me. By the time we meet them, the Yok Huy have been firmly established as the original rulers of Tural. We see many of their ruins as we explore Urqopacha and Kozama’uka, (and many more as we journey through Yak T’el, too,) and as we explore we gather bits and pieces about the legend of their conquest of Yok Tural and their journey into the continent’s northern half, Xak Tural. I’m happy to say this setup pays off with the first bit of Dawntrail’s story that I could sink my teeth into, though it’s a bit of a shallow bite. While potentially interesting, in practice our dealings with the Pelupelu and the Hanu Hanu are low impact and drawn out to the point of excess. The worst example of this is the fact that the actual feat which Wuk Lamat has to undertake for the Pelupelu frustratingly takes place entirely offscreen. (We only help her with gathering the supplies she needs to actually complete it.) The Yok Huy, on the other hand, finally sees us truly taking an active role in the Rite of Ascension. Our task is to find their elector, who’s left their primary settlement. The catch is, the Yok Huy are forbidden from directly telling us where he is. They can tell us where they might have seen him, but not where he’s gone, so it becomes a game of gathering information and following a trail of breadcrumbs that leads us to sites of great cultural significance to their people. The effect of this is that it both teaches us about the Yok Huy and this upper region of Urqopacha simultaneously, and it’s during this journey that we finally see an immensely important aspect of life in Tural that we hadn’t been shown up to this point.

Earlier, I mentioned what Wuk Lamat’s goals as a ruler were - she wants to preserve the peace her father worked so hard to build. The problem here is that Wuk Lamat frustratingly doesn’t really understand her people. Because she’s lived in the city of Tuliyollal for the majority of her life, her experiences are heavily colored by it. She doesn’t know the reality beyond its walls. At least, that’s what we’re told by the story, and yes there are numerous reasons why this particular line of reasoning doesn’t really work and why her particular goal makes her an unfit choice to be a leader compared to her brothers who each have defined goals of their own, even if they’re poorly defined. However, I digress.

Savvy readers already figured out that the Rite of Ascension is meant to act as a window for Wuk Lamat, and indeed all of the claimants, to peer into the numerous cultures that make up Gulool Ja Ja’s nation. I covered as much in my article on him, how he reveals on our second encounter with him that he didn’t develop the rite to select a ruler, but cultivate one. Unfortunately, when it comes to our dealings with the Hanu Hanu, the Pelupelu, and the moblins, this once again ends up being better on paper than it is in practice, especially for Wuk Lamat. The sad truth is, during her dealings with these people, even though we’re shown that there’s tons of people who support her brothers for numerous practical reasons, none of these chapters in the story of the Rite ever challenge the validity of her assertions that harmony and the powers of friendship and getting to know each other by chatting for a few minutes is the best way to improve. Characters who didn’t see her as a good choice either rapidly come around upon her completing their people’s Feat, or their reasons for supporting Koana or Zoraal Ja over her simply aren’t touched on again.

This changes when we encounter the members of a splinter tribe of Yok Huy who don’t agree with tribe we’ve been dealing with to this point. Sort of. You see, as I mentioned earlier, the Yok Huy were once the conquerors of Tural. Using their incredible size and strength, they swept across Yok Tural and subjugated all in their path. This only stopped when they traveled north to Xak Tural, where they were decimated by unfamiliar diseases and forced to retreat to the highlands of Urqopacha. The Yok Huy who we interact with for the sake of the Rite are those who’ve accepted Gulool Ja Ja’s rule and live as distant citizens of Tuliyollal. These new ones we meet, who are conveniently wearing red to indicate their hostility, wish to return to their old ways of conquest and see Tuliyollal, and thus Wuk Lamat’s claim to the throne, as wholly illegitimate.

It marks the first time in the story where Wuk Lamat’s views are actively pushed back against, and it’s nice to see her forced onto the back foot for a genuinely strong narrative reason. There have been brief moments before this where she’s been forced out of her comfort zone, but it’s generally surface level narrative wherein she realizes she either doesn’t know as much as she thinks, or isn’t as competent as she’s trying to come off as. The overwhelming majority of the time, these situations are solved with the tried and true Shonen protagonist method of talking to the person until they conveniently come around to her way of thinking not because she presented some compelling argument or genuinely aided people in a meaningful and practical way, but because the plot deems it so. It’s one of the most major weaknesses in the story, and we’ll expand on it more later. In this case, that’s not exactly what happens. When we meet this trio of Yok Huy, they’re ready throw down and demand that we leave. We try to talk with them, but they won’t be convinced, especially since we’re seeking to ascend to the summit of the tallest mountain in Urqopacha, which is considered one of a few holy sites for them.

This has all the markers of a great situation for Wuk Lamat to be put into. Here we have a group of people who vehemently disagree not only with her, but the entire nation she purports to represent. As a sect of their people who wishes to return to their original traditions, they see Tuliyollal as illegitimate and have no interest in pretending to see things from Wuk Lamat’s point of view. This could have presented her with a great lesson in the realities of multiculturalism, the fragmentation and separation that naturally occurs as people self segregate amongst those they tend to view as their own. It should have presented Wuk Lamat with a serious challenge to her worldview, forcing her to question her approach and grow. So, how does this resolve?

Unfortunately, not nearly so interestingly as it begins. It’s a chance encounter with dangerous local fauna, a large bird that nests on the mountain, that forces these Yok Huy to back off. As the characters are arguing their sides, this avian menace swoops down and injures one of the Yok Huy, who only escapes death because our long time companions, the twins Alpinaud and Alisaie, jump into action to defend all present from this monster’s ambush and heal the injured giant. Out of respect for the good gesture, they opt back off, supposedly remaining in their refusal to accept Tuliyollal as the legitimate government. I say supposedly because apparently they’ve decided this single gesture is enough for them to allow everyone to ascend the mount they were about to try and kill us for approaching just a few minutes ago. While I understand the injured Yok Huy being willing, to have the far more zealous compatriot of his who was doing most of the talking allow it so easily felt a bit farfetched.

Nevertheless, we ascend the mountain to continue the feat, playing through our ascent in a dungeon that concludes with us facing off in combat against the Yok Huy’s chosen elector. I have to say, despite the story stumble that led us here, I very much enjoyed this dungeon. It’s the first time in the story of the Rite where we as players take a genuinely active role in the completion of a Feat, leading to a very welcome moment where the impacts of gameplay and story work in tandem to make the whole of the experience greater. This technically continues into the next Feat, which was also to be handled by the Yok Huy and leads us into our first Trial, an 8 person boss battle against a powerful enemy. The enemyin this case is the monster Valigarmanda who, despite a name that sounds more at home in India, is effectively the Mayan serpent deity Kukulkan.

Unfortunately the leadup to this is rushed and clumsy, as he ends up released from his prison of ice by Bakool Ja Ja, the fourth claimant, who’s cemented himself as an underhanded villain by this point. Despite that, the fight itself was decently enjoyable and surprisingly challenging for the normal mode version of a Trial. It’s just a shame that Valigarmanda’s part in the story is so low impact, not just because of the manner in which he was released, but also because we once again don’t actually get to see the damage he causes ourself. The most we get is a brief flashback sequence as we’re shown Bakool Ja Ja’s treacherous deed. We don’t get to see any of Valigarmanda’s rampage across the mountains.

Once Valigarmanda is defeated, we move to the third and final area of Yok Tural, Yak T’el, where we partake in the final two Feats. The first of them unfortunately throws back to the same low impact issues that plague the Hanu Hanu and the Pelupelu. It involves meeting with the cat-like Xibraal, (pronounced shib-rahl) Wuk Lamat’s own people, wherein the claimants and their supporters will be paired into teams to figure out and recreate a staple local dish, Xibruq Pibil. Literally, it’s just Final Fantasy’s version of the Brazilian dish, Conchita Pibil, and while this segment of the story does detail the interesting history of conflict between the feline Xibraal and the lizard-like Mamool Ja who live nearby, it does so in a manner that’s both incredibly boring and padded out with a multistage talk-and-fetch quest, something which we’ve seen numerous times across this expansion so far.

As expected, Wuk Lamat excels in this, as does her brother Koana, who was made to team up with her. Zoraal Ja and Bakool Ja Ja, each of whom are prideful, warlike, and have zero interest in this, naturally fail. This leads to an event I’ll discuss in greater detail later, as it’s something that I take a great deal of umbrage with on a narrative level, so again, keep this in mind as we journey deeper into Yak T’el, to the darker parts of the lower forest that’s full of flora which glow with an ethereal blue thanks to the effects of ancient meteors that struck this land thousands of years prior. This area is the ancestral home of the Mamool Ja, Gulool Ja Ja’s people, though the remnants here are no great fans of his. Upon exploring this area and meeting with the people in this region, we find ourselves shunned by them. No one is willing to speak with us beyond telling us we’re not welcome. Eventually we find our way to a ziggurat at the end of the settlement, where the elector waits for us.

This encounter gives us a few key revelations. First and foremost, we see that Zoraal Ja, as has been the case for much of the Rite, has beaten us here. However, where his strength and combat prowess allowed him to excel in all cases except for the previous Feat, we find him here kneeling and winded before a fading shadow of his father when he was in his prime. This, we learn, is the test put before us by the elector. The leader of these Mamool Ja seeks to return to the old ways, where a two-headed Blessed Sibling like Gulool Ja Ja or Bakool Ja Ja would rule over all of Tural. We also learn soon after that this man is Bakool Ja Ja’s father, who sought to install his son on the throne so that the Mamool Ja would be elevated above all other people in Tuliyollal. Unfortunately, Bakool Ja Ja has lost his desire to compete in the Rite, as he was just defeated by Wuk Lamat in single combat. (We’ll get to it.)

As you might expect, this segment is one of the heavier parts of the story. It’s here that we finally learn Bakool Ja Ja’s true motivations, as well as his true feelings about what he is and the culture he lives in. Personally, a lot of these revelations were too little, too late for me, as for the entirety of the Rite story before this point he was portrayed as a repugnant prick. That said, the motivation and his character writing, as well as the interactions we get to see with his mother, are comparatively decent even with this pitfall. Through his revelations and our following investigations, we learn the dark secret behind the Blessed Siblings and why the traditionalist Mamool Ja who remain in their ancestral home are so desperate to breed them in order to reclaim power. The forest they live in, thanks to its dense canopy, low elevation, and the particular aether seeping from the various meteors in the area that give the plants their blue glow, is a place that makes it extremely difficult for them to cultivate foods other than a small handful of local plants that can be farmed, such as a unique species of banana that they grow. This was the driving force for their conflict with the Xibraal, who live in the sunnier upper forest - the Mamool Ja sought arable land to claim for themselves.

The first of the Blessed Siblings was born in this time, the result of a political union between two of the three subspecies of Mamool Ja that was enacted in an effort to reduce their own infighting. Got to love tumultuous cultures like that, right? In any case, this was a game changing event, as the power of the Blessed Siblings proved to be just the secret weapon the Mamool Ja needed to start turning the tables in their favor. Ever since then, and especially since the founding of Tuliyollal by Gulool Ja Ja, considered to be the single greatest of the Blessed Siblings in history, (though this claim does clash with the distaste these Mamool Ja have for him) these traditionalists have been desperately trying to breed more of these rare two-headed powerhouses in order to reclaim control for themselves.

Sadly, we learn that the rarity of these Blessed Siblings isn’t because the union of these two different Mamool Ja subspecies is difficult. In fact, it seems that a good many children born of this union end up as two-headed siblings. So why are there so few of them? That’s revealed to us by Bakool Ja Ja’s mother, who bids us speak with her on the edge of town once her enraged husband banishes their son for his failure to obtain the keystones needed to complete the Rite, means of obtaining them be damned. She leads us to a cenote, a kind of sinkhole, on the far end of the forest. A path has been built leading down into the underground cavern and, after hitching a ride on the back of some hippogryphs, we find Bakool Ja Ja mourning over the underground lake at the bottom of the cenote. Weeping and broken, his mother bids him to reveal the truth to us, about both the Blessed Siblings and his actual wants. Bakool Ja Ja agrees and, reaching into the water, he removes a large urn, one of many that we can see strewn about the lake.

As it turns out, each of those urns contains a Blessed Sibling, one who died in infancy. There are literally thousands of urns in this lake and the burial grounds that lie along the path beyond. This is the truth of the Blessed Siblings: while they’re actually quite easy for the Mamool Ja to birth, only about one in a thousand actually survive past infancy. Bakool Ja Ja tells us this, then reveals the truth of his motivations. He doesn’t actually care about ruling, he just doesn’t want any more children like him to be born into the world only to die. It’s a grim turn in the story, and while it comes too fast and too late to redeem Bakool Ja Ja in any way, it still manages an emotional punch and adds necessary stakes to the mission of finding a way for the Mamool Ja traditionalists to make better lives for themselves in their ancestral home.

This culminates with us returning to the ziggurat to finally face Gulool Ja Ja’s shade in a mock Trial that pairs you with Wuk Lamat, the twins Alphinaud and Alisaie, as well as Koana and your longtime companions Thancred and Urianger, who took up the offer to assist him in his claim. The story in this area is a bit rushed, which is unusual considering how earlier portions tended to drag things out too long, but on the whole it’s a decent showing. Coming out victorious from the battle, Wuk Lamat claims her final keystone and we journey back to the cenote where the Blessed Siblings were laid to rest, having realized that this is the only place we’ve found where the fabled City of Gold could be hiding. We head there, run through yet another dungeon directly tied to the Rite, and upon finding the entrance we find Gulool Ja Ja waiting for us, where he congratulates his daughter on a job well done and we return to Tuliyollal to see her crowned as their new Dawnservant.

As you can see if you stuck with me to this point, there was a lot to cover in that first half of the story. However, for as much as there was to talk about there, it’s quite impressive just how little of substance actually happened, particularly when compared to the story’s second half, where a major turning point takes place.

Testing the Player Base

At the start of this review, I mentioned that my reasons for writing these articles were self serving. I say this because I think Dawntrail’s main story stands as something of an A/B test. The reason I think this is because of how wildly different the two halves of the story are. I believe the team want to get an idea of what sort of stories the players want to see going forward, which seems to be supported by how much attention they’ve seemed to give to feedback on the story so far.

From what I’ve told you of the first part of the story above, you probably gathered that the Rite of Ascension part of the story is largely pretty light. It’s a lot of smaller impact and more isolated events with a much lighter overarching plotline to follow. There’s hints of adventure, attempts at humor, and generally a more jovial and relaxed feel to the whole thing, apart from the portions where we deal with the Yok Huy and the Mamool Ja. Particularly the Mamool Ja. Taken as a whole, the first half’s plot is simple and straightforward, its resolutions quick and convenient. Unfortunately, serious issues of pacing and characterization also make a colossal portion of it an absolute slog to get through.

But what about the second half?

I’m happy to say that the second half improves in a number of ways, though it also bears its own major pain points. This portion begins by having us travel to Shaaloani with Erenville, after the coronation of Wuk Lamat and, surprisingly, Koana as well. This is a welcome bit of character growth we get to see in Wuk Lamat, the recognition that for all her exuberance and stated care for her people, she’s still not fit to rule Tuliyollal alone. As such, her first decree is to announce that she won’t be the only Dawnservant. Much like their adopted father ruled by matching his Head of Resolve with his Head of Reason, Wuk Lamat and Koana together will carry on a similar legacy as the Vow of Resolve and the Vow of Reason respectively, acting as a fair capstone to that arc of their stories.

Now that the coronation is finished, Erenville is eager to travel northwards, journeying into Xak Tural in order to return to his home, a village called Yyasulani. As it turns out, despite the fact that we meet Erenville in Old Sharlayan way back at the start of Endwalker, he’s actually a Turali native who traveled there at the behest of his mentor and mother, a woman named Cahciua, who was also one of Gulool Ja Ja’s traveling companions when she was younger. Being a gleaner, which is a type of field researcher meant to gather flora and fauna specimens for the Sharlayans, Erenville is knowledgeable about the behaviors of dangerous beasts and therefore able to avoid fighting with them, but he’s not combat trained himself. For this reason, as well as the fact he knows we’re itching to carry on with a proper adventure, he asks our characters if we’d like to travel with him, which we accept. Thus begin our Wild West travels in Shaaloani.

There’s not much for me to say in regards to the Shaaloani story that I haven’t already. It’s small, self contained, and apart from a couple moments where the writing team pulls their punches1, generally a fun Wild West adventure story as I alluded to in the previous section. In other words, it was the exact sort of light and generally enjoyable story I was hoping to get in this expansion.

What really helps this portion is Erenville himself. He’s the quiet, awkward, slightly dour type, but unlike a great many characters these days who carry these traits, Erenville is quite likable. These particular traits are paired with a biting but friendly wit, and care is taken to show that he has quite a passion not only for his profession as a gleaner, but for the wellbeing of animals in general. It’s little wonder, then, why he ended up as a popular character with quite a few ladies among the player base. (And presumably gay guys, too.) Paired alongside the self contained adventure story and a goofy throwback to the much beloved Shadowbringers expansion, our trip through Shaaloani with Erenville provides not only some much needed breathing room, but a much needed shift of focus back to us, the player. The self contained stories in this zone aren’t deep or complex. In fact, they’re very predictable, but that doesn’t matter because this little moment in the spotlight, as well as the breathing room this segment brings, is beyond welcome after spending so many hours being slowly dragged through most of the Rite of Ascension story with little of significance to do.

But this part of the story is ultimately just a palette cleanser, a way of clearing the room so the second portion can begin. Upon assisting the local rail company in petitioning the native Hhetsaro (Tural’s name for the Miqo’te, the game’s original cat people) to trade for much needed lumber to repair their tracks, we prepare to set forth to Yyasulani on the second train going out. However, while the first one is away, an alarming incident occurs, because of course it does. This is Final Fantasy, there’s always an alarming incident to break the calm. In this case, said incident is the very sudden appearance of a massive dome of crackling energy on the other side of the rolling mountains along Shaaloani’s northern border. If you know anything about writing, you already know exactly where this dome appeared - Erenville’s home, Yyasulani. To make matters worse, a small fleet of strange and technologically advanced airships emerge from the dome, making a southward bee-line for Tuliyollal.

Naturally, being an experienced world saving hero, we hurry back to the capital to find it being stormed by highly advanced and durable machine soldiers whom the local guard and a smattering of mercenaries who work out of the city are struggling to push back. The event is reminiscent of the midpoint of Endwalker, where we return to the starting zone of Thavnair and its attached capital, the bright and colorful city Radz-at-Han, only to see the sky awash in swirling smoke as fire rains down from on high and hideous monsters fill the air. We also see the gruesome effects that the terror of the Final Days causes on people. As the disaster spreads, we witness firsthand the citizens turning into the very monsters that assail them, and later realize that it’s their very fear and despair which is leading to this change. It’s a harrowing and powerful segment of Endwalker’s story that plays well against the much more lighthearted introduction we got to this region at the beginning.

Unfortunately, I can’t say the invasion of Tuliyollal is nearly as effective. I won’t dig too deep into why just yet. For now, let it suffice for me to say that my investment in the goings on of Tuliyollal haven’t been nearly so well established as my investment in Thavnair and Radz-at-Han were. Part of the reason for this is the revelation of who leads this attacking force, a reveal that isn’t very surprising, but also leaves us scratching our heads at the suddenness of this heel turn: Gulool Ja Ja’s natural born son, Zoraal Ja.

Now, it does make sense for Zoraal Ja to enact some sort of a coup attempt in Tuliyollal based on what we’re told. Keep this phrasing in mind: based on what we’re told. He’s their ruler’s only natural born child, viewed himself as the rightful heir, is frequently stated to be war hungry, and yet was still forced to compete with his adopted siblings for the throne. A competition which he lost when he failed both of the Feats in Yak T’el. It makes sense that he would be incensed by this. Given that the narrative keeps poking us with reminders that Wuk Lamat believes he can’t be allowed to take the throne because he wants to enter an age of conquest, it’s not exactly a shock to see him come back with this advanced army when its also been revealed to us that he cheated his way into gaining entrance to the City of Gold after we visited there.

Where the head scratching comes in is with his motivation. It used to be that he wanted to rule Tuliyollal and engage in conquest first on a continental, then on a global scale. His stated reasoning for this desire was to teach the people of the world the horrors of war so they’d appreciate rule in an era of peace. I’m paraphrasing there, but that’s effectively what his goals are. If you can wrap your heads around it, more power to you. For me his stated motivation never made sense, and since he wasn’t exactly personable in any way, it always made me wonder why the hell so many people supported his bid for the throne.

Well, his motivation seems to have changed somewhat. Now he doesn’t particularly want the throne, he wants to crush Tuliyollal underfoot and prove he’s superior to both of his adopted siblings and to his father. In fact, when we finally see that it’s a cybernetically enhanced Zoraal Ja who’s leading this force, it’s while he’s engaged in combat with Gulool Ja Ja. Now I’ve touched on a few times across this essay so you already know there’s been a few pain points across Dawntrail’s narrative so far. Some are minor, a few are major, most are moderate. This moment unfortunately marks one of the most major issues, and while I know you’re probably itching for me to get into it now, I ask for a little patience. We’ll go over all of that in the next section.

In any case, father and son fight, and the son is seemingly struck down only for a device attached to the side of his head to ping, flare to life, and apparently bring him back from the dead. The fight resumes, this time with Zoraal Ja drawing additional power from this device, and he strikes his father down. Yes, sad though I am to say it, the very character that I was just praising a few weeks ago as one of the few strong father figures in a modern fantasy story gets killed by his ambitious son. What follows is Zoraal Ja stating his desire of his siblings, especially Wuk Lamat - seek him out inside the dome. There they’ll face each other, and in so doing prove who is truly the most worthy ruler. Then he and his army leave, teleported away by this advanced tech he’s gotten his scaly hands on, while leaving the retinue of ships he brought with him behind to remain as a literal looming threat over the city.

Thus does the second part of the story begin, and as you can already see the tone is very different. In terms both of the writing style and the type of story it’s trying to tell, it’s far more reminiscent of the familiar ground we’ve walked in Heavensward, Shadowbringers, and Endwalker as well. And despite the major issue that does come up with this introduction, it’s also a generally stronger story than the first half. Let’s look at why.

This second half of the story, as you might expect, takes us into the strange energy dome that appeared over Yyasulani. It sees us traveling with our long time allies from the technically now defunct Scions of the Seventh Dawn, as well as with Wuk Lamat again because we just can’t seem to be free of her, to break our way through the fortified facility that grants access to the dome and explore the fifth zone which I mentioned in the prior section, Heritage Found. The photo that opens this section is taken from that zone. As can be seen compared to the other pictures I’ve shared so far, it’s hardly the kind of sunny and colorful place that we’re shown in much of the first half of the story.

After working with the train company to convert their train into an armored breach bomb - which for inexplicable reasons is constructed in a montage featuring the song Smile, a gospel styled ballad of kindness and togetherness that’s also used as the end credits theme for Dawntrail’s main story - our team fights through the fortress at the edge of the dome and gets inside, where we then find the ruins of Yyasulani Station. While everyone in our group is shocked by this, no one is more taken aback than Erenville. This area was his home, after all, and while he’s only been away from it for three years the remnants of both the station and the other settlements we find there look like they’ve been abandoned for ten times that long.

We begin to explore and investigate, making our way down the road to where Yyasulani should be. Naturally, Erenville is incredibly worried about the fate of the people he used to know here, his mother in particular. Wuk Lamat shares his worry, as well as worry for her former nanny, a woman named Namikka who had taken the first train headed out to Yyasulani, as she planned to visit family and possibly retire there. The hope is to find signs of survivors, or at least evidence of what the hell happened here. We know that Zoraal Ja had something to do with the dome appearing, and we know that he’s likely residing somewhere in the massive tower that reaches up into the perpetually lightning-filled sky, but little else.

Imagine our surprise, then, when instead of finding survivors in this lightning blasted wasteland, we meet a queen, of all people.

This is Sphene, the Queen of Reason and ruler of the nation of Alexandria, a land that none of our characters have heard of before. Sphene explains to us that, alongside Zoraal Ja as the King of Resolve, (notice how he assigned the titles based on his father’s status as a Blessed Sibling, where Gulool Ja Ja’s two heads were named Gulool Ja Ja the Resolve, and Gulool Ja Ja the Reason) she rules over what remains of her old kingdom, which now includes the survivors and descendants of the Turali people from Yyasulani. Sphene presents as a kindly person who deeply loves her subjects, enough so that she’s willing to leave the Everkeep - the massive tower that looms over everything in Heritage Found - to walk among the Outskirts and check up on her subjects. We later see her doing the same throughout Solution 9, the massive, Tron-styled residential district of the Everkeep which acts as our second major city in this expansion.

Through our interactions with Sphene and the people of the Outskirts, we can see quite plainly the love she has for her people. She genuinely cares about their wants and needs, even going so far as to offer to help them with work that needs doing. Where Zoraal Ja is wholly focused on accumulating his military might, Sphene’s dedication is to the wellbeing of her citizenry. This then raises a natural question - why is she ruling alongside Zoraal Ja? Well, according to Sphene, when they met after he broke his way into the City of Gold, there existed the opportunity for a mutually beneficial partnership. Sphene’s homeland and her entire world had been ravaged by a calamitous surge of thunder aether. Much like how the Flood of Light destroyed most of the First in Shadowbringers, Sphene’s world is a reflection of our own, one that was created when the world was sundered millennia ago in the days following the collapse of the Ascian civilization and all but destroyed by a similar calamity. As such, she desired safe haven for her people. In exchange for this, Zoraal Ja would be made Alexandria’s king and given access to their advanced technology. Most notable of these is electrope, a highly conductive form of stone that the Alexandrians figured out how to manipulate to channel the rampant thunder energies of their world into all sorts of useful marvels. Lest you wonder, electrope is the reason why Solution 9, the Everkeep, and the Outskirts all have far more advanced technology than anything else seen in Tural.

Unfortunately for Sphene, Zoraal Ja’s ambitions didn’t end with becoming the King of Resolve, and he started turning much of her resources towards building and empowering his army. Sphene now wishes to stop this and, knowing who we are thanks to her close relationship with Zoraal Ja, points us in the direction of a resistance movement that’s headed in secret by none other than Erenville’s mother, Cahciua. Thus we begin exploring Heritage Found and Solution 9, working alongside Cahciua and her team to find a way to confront Zoraal Ja directly.

During all of this, we learn that the reason why the old structures of Yyasulani appeared to age thirty years in the span of a few days is because they have, in fact, aged for thirty years, as has everyone under the dome. This lines up with established lore from Shadowbringers, which already detailed that the flow of time between the Source, which is our world, and its various shards does differ, but will line up for brief periods. In this case, since the dome acts as a fusion between Alexandria and the Source, once the timelines balanced out, everything within the dome fully synced to our own flow of time. And as we find out when we find Wuk Lamat’s nanny Namikka as an old woman on the verge of death, this does mean many of the people originally from Yyasulani have died.

It’s for this reason, as well as a pretty surprising reveal that happens about halfway through our exploration of Heritage Found, that this zone is arguably the strongest in the expansion in terms of story. As we unravel the mystery behind Yyasulani, the dome, the Everkeep, Queen Sphene, and Zoraal Ja’s ambitions, we also find ourselves finally beginning to explore the stronger personal stories in Dawntrail, and Erenville’s is arguably the best of them. As we work alongside Cahciua and her rebel front, we soon discover that not all is as it seems with her. Apart from the fact that she spends this part of the story working with us remotely through a little hovering robot, Erenville eventually discovers that some of his old friends did survive what happened in Yyasulani and moved into Solution 9. However, when he questions them about where Cahciua is, nobody is able to remember her.

This reveals an important cultural detail we learn about Alexandria - their use of souls to prolong their lives. Through their advanced technology, the Alexandrians effectively recreated the effect that happens naturally to those who die in this setting. Normally, when someone in the FFXIV world dies, their soul returns to the Aetherial Sea, where their life force returns to the planet and their memories drift along the aetheric currents, thus creating a form of afterlife for them. The Alexandrians mechanized this process, storing life energy for people to reuse, while saving their memories in a terminal that allows them to be drawn upon for the sake of being recreated. This technology is why the device on Zoraal Ja’s head allowed him to be revived after Gulool Ja Ja struck him down in their fight, and it’s why the former citizens of Yyasulani don’t remember Cahciua. As a means of making it easier for them to cope with returning from death, anyone wearing the regulators on their heads will have not only memories of their own deaths altered or erased, but the memories of passed loved ones erased as well, all to spare them pain. It’s a thoroughly dystopian means of maintaining happiness that reminds me in some ways of Brave New World, and the utter shock at this difference in culture, showcased by the likes of Erenville and our companion Alisaie, account for some of the better character moments in this expansion.

In any case, as we explore Solution 9 Cahciua’s team informs us that an opportunity to strike at Zoraal Ja has come. He’s gathered a new force and is about to lead it against Tuliyollal again. Planning to use his desire to prove his superiority against him, we head out with Wuk Lamat to help to watch her back as needed while she duels him directly. However, we find that Queen Sphene is also with him, and in our discussions we learn that she’s not the ally we were lead to believe. Zoraal Ja tells us that in order to preserve her own people, Sphene’s been working with him on this plan of conquest so that she can claim the souls of those killed on our side in order to preserve the resurrection process for her own people, in particular the Endless, a caste of Alexandrians who’s forms are perpetually maintained after death with the life energies of people’s souls.

Unfortunately for Sphene, she also learns in this moment that Zoraal Ja has no interest in seeing her plans through. When Wuk Lamat destroys his regulator in their duel, rendering him vulnerable, he immediately strikes down the nearest living Alexandrian to steal his regulator for himself, then orders the ships he left behind to raze Tuliyollal. His attack fails, though, as while we’ve been away, Koana’s been hard at work reaching out to would-be allies and working with Old Sharlayan to help bolster Tuliyollal’s defenses. In the end, it’s the allies he made in Radz-at-Han who turn the tide, in particular their leader, the dragon Vrtra (pronounced vree-trah) and his brood, which is little more than a shoehorned excuse for a callback to a well liked character from the previous expansion.

Enraged, Zoraal Ja orders his mechanical army to turn their guns on the people of the Everkeep, much to Sphene’s despair. Begging us to help save her people, we agree to return to Solution 9 with Sphene and fight our way through Zoraal Ja’s forces to save what people we can. Once the fighting is done, we work with Cahciua and her people to fight our way to the top of the Everkeep and face Zoraal Ja ourselves. Hypercharged with aether from the souls he consumed, his body transforms into a monstrous form and we lay him low, as we’ve done so many other would be gods and monsters in the past. On his deathbed, he finally reveals why he did everything he did - a feeling of inadequacy. Despite the fact he was Gulool Ja Ja’s only natural born child, which itself is miraculous since two-headed Mamool Ja are usually sterile, he believes he was given nothing in his life.

You know, daddy issues. I’m not at all ashamed or afraid to say that I was downright pissed off when I watched the cutscene where he lays out this justification. Even when other characters called him out on his bullshit, it still sat ill with me. Zoraal Ja, and us players as well, are told that he was the one most favored by his people, and Gulool Ja Ja had no shortage of love for his only true born son. Wuk Lamat lays into him for his feelings of false inadequacy and his choice to throw everything away to try and fill a void that didn’t need to be there. It should be compelling, yet all I found myself thinking in this moment was how wasted this character was because the story never shows us this aspect of Zoraal Ja. Just like with Bakool Ja Ja, there’s not nearly enough buildup to this reveal. At no point in the earlier story are we shown anything to indicate that Zoraal Ja harbors these feelings, and that makes it impossible for this landing to stick.

And then there’s Sphene, who shows up after he dies and promises to carry on with the plan to wipe out life on the Source so she can use their aether to maintain the lives of the Endless Alexandrians. By this point, thanks to Zoraal Ja supposedly killing her just before Wuk Lamat’s duel with him earlier, we’ve already had it revealed that Queen Sphene isn’t actually alive. Rather, she’s one of the Endless, and the Sphene we’ve seen is a digital construct built from her memories. The Sphene we’ve been walking around with this entire time has, in fact, been a projection overlayed on top of the body of a mechanical soldier. Sphene takes the key that Zoraal Ja stole to access the City of Gold, which is in actuality part of her home shard, and returns there herself to begin the process of interdimensional fusion. Basically, her plan is to take what happened to Yyasulani and expand it to the rest of the world, overlaying her shard onto the Source and killing most of the people there in the process. If that sounds suspiciously similar to a rejoining to those of you who’ve played the game and know what the plans of the Ascians were, that’s because it is.

Naturally, we can’t abide this, so we return to Yak T’el, make our way back to the entrance of the City of Gold, and cross to the other side to try talking Sphene out of her plan one last time. She and Wuk Lamat have bonded some by this point, and since both of them ultimately share the goal of peace for their peoples, Wuk Lamat hopes that she can talk Sphene down and they can work out a way for their nations to coexist.

I can honestly say that the City of Gold is not what I expected when we finally gained access to it. The cityscape they show is simultaneously reminiscent of Blade Runner, Metropolis, and Disneyland, and we quickly discover that this entire region - dubbed Living Memory - is effectively a colossal amusement park for the Endless to live out their reconstructed lives in pleasure and happiness. It has the potential to make for an interesting juxtaposition against the threat that we face, and our mission here ends up being pretty simple - travel to each of the four zones within Living Memory and shut down their central terminals. Once that’s done, return to the Meso Terminal, the centermost terminal where Queen Sphene is in the process of rewriting her memories so she’ll be better able to conduct her genocide without feelings of guilt, and face her in there so that we can halt the dimensional fusion before it happens. And who should be the one to present us with this plan?

Why, none other than a ravishing Shetona maiden - her words, not mine - by the name of Cahciua.

Yes, at long last we get to meet Erenville’s mother in the flesh.

Kind of.

Not really.

Upon meeting her, Cahciua confirms our suspicions that she is no longer alive and has, in fact, become one of the Endless. In so doing, she explains to us how it is that Living Memory works - the terminals create aetheric constructs of the Endless for them to live out lives of happiness and leisure. However, they’re not truly living. The constructs are built based on the preserved memories of these long dead people, folks who’ve also had their memories altered across their lives based on the norms of Alexandrian culture. Against the soft gold skyline, colorful and cheerful “lands” the people are enjoying themselves in, and the gentle-to-the-point-of-sleepy music, this notion comes off as quite grim when you stop to think on it.

Alas, neither the story nor the gameplay, what little there is, we’re given in Living Memory does very little in terms of pushing us to think on this gruesome dichotomy. The inherent vapidity of an entire afterlife constructed almost solely of material pleasures is never once touched upon, while most attempts at wringing out meaningful stories out of the few characters we meet here falter and, ultimately, fail. Where we could have had an experience that asked our characters and companions to consider the deeper implications of death, afterlives, and what exactly constitutes the soul, we instead spend our time traveling between the four “lands” and speaking with the Endless in order to shore up our understanding of who they are and why Sphene is so determined to preserve them. By the by, the lands are as follows:

Canal Town, which is calm, Venice-like leisure area full of parks, walkways, and obviously, canals with gondolas to sail upon.

The obviously Disneyland inspired Yesterland, which looks like a grand castle town.

The extremely confusing Asyle Volcaine, which is simultaneously home to a battle arena, a safari park style zoo, and a fake volcano that, for reasons beyond any narrative sense, houses a museum that details the history of the milala, Alexandria’s version of the diminutive lalafell race. Why they have this museum inside the volcano is a complete mystery to me, since none of the lore they reveal here relates to volcanoes in any way.

Finally, there’s Windspath Gardens, which is exactly as it sounds like: a massive garden and arboretum full of winding walkways for the Endless to explore. It’s also the most beautiful and interesting of the four lands in my opinion.

Of all the regions we visit in the expansion, Living Memory is probably the most disappointing. The zone basically has four different goals that it wants to achieve:

To help you understand the kind of lives the Endless are leading and the problems Living Memory is facing thanks to the aether shortage.

To showcase the history of Queen Sphene’s life and the major impact the calamity had on Alexandria before she died and became one of the Endless herself, as shown both in the Yesterland portion of Living Memory and in the final battle with Sphene herself.

To conclude the story of Krile, whom I’ve not mentioned yet. There are reasons for that, and I’ll touch them in the final section.

To conclude the story of Erenville’s search for Cahciua.

All of these should have been important and impactful moments in the story, as all of them are key either to the greater story of Living Memory, Alexandria, and Queen Sphene; or are key to characters we’ve been traveling with across the course of this entire journey. As an introduction to Living Memory and the Endless, I found Canal Town to be competent in this. It reveals some interesting tidbits lore to us, such as the fact that the simulated food the Endless consume has texture but no flavor for living people like ourselves because the flavor of the foods is reliant on the memories the Endless have of them. It also shows us what the cultural goal of Living Memory is, which is to give the Endless second chances at achieving things they couldn’t in life, while allowing them to live in a constant state of comfort. Canal Town showcased this by having us help to reunite a pair of lovers who wished to marry, but weren’t able to due to an accident killing the man when he was young Through a stroke of luck, the memory rewriting effect of the woman’s regulator didn’t fully take effect, leaving a shadowy feeling in the back of her mind of someone important whom she once knew. That memory was reconstructed upon her recreation in Living Memory, allowing him the opportunity to finally propose to her after dying and waiting in Living Memory for a century for her recreation. It’s a simple and heartfelt little tale that reinforces the reasons why Sphene is willing to go so far for her people, and works well enough as a brief introduction.

Yesterland and Asyle Volcaine, however, were complete duds for me. The stories they tell aren’t particularly interesting, and by the time I finished with Yesterland, I came to the unfortunate conclusion that the deeper questions which Living Memory begged simply weren’t going to be answered. This blow became a one-two punch because the race against the clock we’re supposed to be involved in, which is the race to deactivate the terminals before Sphene finishes rewriting her programming in preparation for global genocide of the Source, was painfully shown to be a complete non-issue in the narrative sense. I never once felt that we had to move quickly in order to finish this supposedly vital task because the story never once bothered to make me feel any sense of urgency here. Thus, Living Memory took a huge step backwards, right into the sort of muddy slog that the Rite of Ascension story was.

0I will admit that by this point, I’d become extremely frustrated with how much the story of Dawntrail as a whole had dragged its feet through that mud. By the time I was finished with Asyle Volcane, I was genuinely ready to throw up my arms and skip every remaining cutscene. The only reason I didn’t is because I knew Erenville’s portion of Living Memory was coming, and his was the only story that genuinely managed to draw some investment in me. Fortunately, I can at least say that Windspath Gardens finally returned us to something resembling a more traditional mode of questing while also presenting the single most compelling story beat in the entirety of this final act.

Erenville having to come to terms with the fact that not only is his mother actually dead, but now we have to erase the extremely real feeling construct of her that remains, is by far the best portion of Dawntrail’s main story quest. I’m not only happy, but relieved to say that being able to take part in the interactions between Cahciua and Erenville in Windspath Gardens is equal parts heartwarming and heart wrenching, giving us the best writing of the expansion’s leveling experience. I’d even go so far as to say the emotional impact of our normally quiet and dour friend finally saying goodbye to his mother comes close to reaching some of the game’s most famously impactful moments. It then hits all the harder for the fact that, despite the fact we know the end to this unnatural existence is what Cahciua truly wants, this woman who’s shown herself to react to hardship and pain with a smile and a laugh up to this point finally wells up and sheds tears as she bids farewell to her son for the last time.

The impact of this resonance is enough that just writing about it is getting me choked up.

Yet, while I genuinely do wish I could say that this quality of writing carries through to the end, to do so would be a lie. Once the final terminal is shut down, Cahciua and the projected landscape of Windspath Gardens vanish, just as did the other three sections of Living Memory before it. We then return to the Meso Terminal to finally face Sphene and conclude the story through the final dungeon and Trial.

And it’s at this point that we must move on to the final section.

Dawntrail is a Horribly Inconsistent Mess

I’d like to bring your attention to the character pictured above. This is Krile, who I mentioned near the end of the previous section. Like with the Scions of the Seventh Dawn, Krile is a character that’s been part of this game for a very long time, specifically since the Heavensward expansion. That is to say, she’s a long established member of our expansive retinue, but she never really got too much focus in the story. Instead, she’s been relegated to a secondary, or more often tertiary role. There were moments where her story was brought into focus or given more depth, such as a small segment near the end of Stormblood’s main story, or her involvement with the story of Eureka, a special endgame zone in that same expansion. However, she’s never truly been a focal character before, and that’s something Dawntrail promised to change.

In the final patch of Endwalker, Krile discovers an earring and a letter that were left to her by her grandfather, a Sharlayan researcher and mage named Galuf Baldesion. I’m not entirely sure why she refers to him as her grandfather, since he’s truly more her adopted father, but my guess is that it has to do with the fact that he seems to have already entered his silver years by the time she was passed to him. And I do mean that literally, we’ll get into why very shortly.

The letter is a missive that was addressed to Galuf by Galool Ja Ja himself, requesting he return to Tuliyollal on urgent business. It turns out that Galuf was with Gulool Ja Ja when the first discovered the city of gold, and that earring was a relic he was given alongside Krile when her parents passed through the gate and not only gave her over to him, but also gave the key needed to open the gate along with her.

This is the story we cover with her and her parents in Living Memory, as well as in an earlier cutscene that showcases the moment where her parents passed through the gate. In and of itself, it has potential to be a compelling story that brings lore which further fills out the history of the world and gives Krile a portion of genuine importance within it. Given this is the case, you’d think her story would get a solid chunk of screen time and focus, right? That the endeavors of this character we’ve known since the game’s first proper expansion would be well fleshed out and give us a similar sort of emotional and narrative payoff that Erenville and Cahciua, yes?

Well, if you assumed that as so many of us players did, then you were fooled just the same as we were. While Krile’s story holds some significance to the greater lore of the various calamities which took place across the Source’s history, as well as significant importance to Sphene’s own plans, the amount of screen time and focus she receives is downright miniscule. In fact, she not only receives less speaking lines than Erenville, who was always advertised as a secondary character in this expansion, but less than both Gulool Ja Ja and Bakool Ja Ja as well, and they’re not even constantly traveling with you the way Krile is.

Why is this? To put it frankly, it’s because the presence that she, and indeed everyone in this story has is absolutely paltry in comparison to that of the single greatest story hog in this expansion: Wuk Lamat.

I mentioned in my article about Gulool Ja Ja that Wuk Lamat is unquestionably the main character in Dawntrail, for better and for worse. I would absolutely say that in the vast majority of cases, this decision is for worse, and that’s punctuated by how she not only draws away from Krile’s story, but from our own. Permit me to explain.

Across the course of FFXIV, our character is established as the Warrior of Light, a hero blessed by the Mother Goddess Hydaelyn to battle against the darkness of the Ascians and the threat of powerful monsters such as the god-like the Primals or mighty dragons like Nidhogg, who is one of the primary antagonists in the Heavensward expansion. While there are many characters involved, such as the Scions of the Seventh Dawn, the rulers of the various nations of our home continent of Eorzea, the villains of the Garlean Empire, the Ascians, and many more who get their own story arcs and moments of personal growth, the story of FFXIV has ultimately been our story. It’s been our adventure, our actions within it that lead to the most change within the world. It’s not a character driven story; our choices won’t affect how the story plays out, but the story has been written in such a way that we’re usually the ones given the agency to deal with the various events, encounters, and enemies across this game. Generally speaking, the moments where this agency is denied us are the moments where the villains have gotten the upper hand on us. It wouldn’t be an interesting story if all we did was win every step of the way, after all.

However, this rule about how our agency is removed isn’t universal across this story. There have been moments across this game’s history where agency has been denied us, where moments that we could and should have acted - especially based on how we usually respond to similar situations at other points in the story - force us to remain stagnant for the sake of the plot. Stormblood took a good amount of heat for this thanks to a number of plot conveniences that were used to either force us into unwinnable situations, or bail us out of them. The most infamous moment of this that I can recall was after we journey into the lands of Gyr Abania, the first place in Eorzea where the Garlean Empire established a foothold. While attempting to find a way to capture a heavily fortified bridge that spans a massive chasm in the Fringes, one that’s equipped with a titanic artillery cannon, that we find out that very same cannon is currently being loaded and aimed in the direction of our resistance team. It’s a situation that leaves us in a position where we are absolutely fucked, requiring immediate action to survive it.

Only it doesn’t matter because the character Estinien shows up out of nowhere, jumps down onto the cannon, and destroys its central firing and rotation mechanisms only to disappear for the rest of the story. I’m saddened to say that Dawntrail commits sins even more egregious than this, and the most frustrating thing about them is they’re all situations that were easily fixable with some simple editing and basic reworks to the story. So, what are the issues present?

Firstly, pacing. Dawntrail’s pacing is wildly inconsistent. The first two Feats we undertake in the Rite of Ascension each take about 1-2 hours to complete when accounting for gameplay and cutscenes. This kind of time taken isn’t necessarily a bad thing depending on what it is you’re doing. If you’re partaking in story events that involve active participation in engaging regional events, such as happened with our introduction to Thavnair in Endwalker, or when we were introduced to the bleak horrors of the First with our initial trips to Kholusia and Amh Araeng in Shadowbringers, then that time passes by quickly and feels satisfying. Dawntrail’s introduction fails in this because the time we spend with both the Hanu Hanu and the Pelupelu involves us running with Wuk Lamat doing menial task after menial task after menial task

And when I say these tasks are menial, I mean it. In the Pelupelu’s case, we spend our time running around with an aspiring young trader of theirs so that we can trade our way up from a ball of alpaca wool to a specialized and very expensive saddle that Wuk Lamat needs to complete her Feat of catching a wild alpaca for them. It’s an activity that’s interesting only on the most basic level thanks to the insights it gives into the Pelupelu culture. However, in terms of the actual tasks you’re engaged in, not to mention the number of steps you have to take to complete the quest chain and the limp nature of the narrative itself, it’s frankly boring as all Hell. You’re not actually doing anything that requires your particular expertise in any way, shape, or form.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m no stranger to menial tasks in MMOs. Many of the quests all throughout FFXIV involve us doing menial work, but in the main story those quests usually build up to larger events which position you and your allies as the ones best suited for the job. Dawntrail misses the mark on this. The Feats of the Hanu Hanu, the Pelupelu, and the Moblins are all things that don’t actually require your involvement at all. Any one of the other characters with you could do the work you’re being made to do. Going back to the Pelupelu specifically, the chain of trades for the saddle is something Wuk Lamat and the girl who offers to help her could do alone. Your presence is justified only by the flimsy excuse that Wuk Lamat is too clumsy and stupid not to accidentally lose what you need to trade.

Similarly, the solution to the Hanu Hanu’s problem of their reed paddies being sickly is something that Alphinaud and Alisaie could easily solve alone, especially since it turns out its a stagnation of aether causing the issue, something with they and you have experienced in the story before, yet is conveniently forgotten about for the sake of Wuk Lamat’s ridiculous plan. Then later, when Bakool Ja Ja comes by to bully the Hanu into forcibly giving him their keystone, we do absolutely nothing while Wuk Lamat runs in to strike at him and he throws her aside with a single effortless swing. Lastly, the task for the Moblins is one that also requires zero involvement from us, as their request of bringing new craftsmen in to work in their workshops is ultimately solved by, you guessed it, Wuk Lamat speaking to someone who she already helped get set up in the trade district of Tuliyollal. There is literally zero narrative reason for us to be there beyond the conceit that we’re “helping” Wuk Lamat with her claim.

Fortunately, as I mentioned in the first section, our dealings with the Yok Huy and the Mamool Ja are better in this regard. These portions give us active reason to be present, as both our combat prowess and the particular kinds of knowledge our character picked up across our adventuring career are directly needed in both of these instances. The same is true of Shaaloani and Heritage Found, though sadly Living Memory backslides on this as touched on earlier.

It’s hard for me to understate how endlessly frustrating it is to have our agency within the story so thoroughly stripped away. However, as irritating as the above instances are, especially when paired with the story’s bad pacing, there are two instances where the removal of our agency in the story are downright unforgiveable.

The first of these comes when Zoraal Ja invades Tuliyollal. Recall the fight I mentioned between him and his father earlier in this essay. In that cutscene, even with all his electrope powered cybernetic enhancements, Zoraal Ja loses to Gulool Ja Ja. However, when the regulator on his head resurrects him, he then uses it to draw on an extra reserve of souls to bolster his power. With this boost, he’s able to overcome his father and kill him by stabbing him through the chest. It makes for what should be a powerful and deeply emotional moment. Gulool Ja Ja is one of this story’s few very likeable characters, and his death should have resonance and impact.

Now if only all of that wasn’t undermined by the fact that our character, the world renown Warrior of Light, someone who has literally traveled to the edge of existence to stop the end of the world, just. Fucking. Stands there.

I can’t describe to you how absolutely furious that made me, especially because the game has already established multiple narrative tools within the lore that would’ve allowed us to see that fight without needing to be there. Chief among these is the Echo, a power granted to those touched by Hydaelyn’s blessing that will allow them to glimpse portions of someone’s past in certain situations. Narratively, it’s a simple way of framing flashbacks in the story, allowing us to be filled in on important information without putting us in a situation where our presence should mean we’d step in to try and avert a disaster from happening. A disaster like the murder of Tuliyollal’s former king by his son’s hand, for example? I can’t understad why the Echo wasn’t used here, why we didn’t walk in on Gulool Ja Ja already laid low and Zoraal Ja gloating to us about how we’re too late as he leaves. It would’ve served infinitely better than slapping us in the face with the ludonarrative dissonance of us standing around like a useless, gawping lump when almost every other instance of this type would’ve resulted in us taking immediate action to try and stop it.

The second instance comes in our final confrontation with Sphene. When we face her memory construct inside the Meso Terminal, after fighting through the final dungeon which presents her reconstructed memories of Alexandria when it was at peace, Alexandria during its war with the nation of Lindblum, and Alexandria after both the war and that reflection’s calamity ravaged and ruined it, she verifies what we’ve already come to know about her plan: she’s going to delete all the positive, kindly memories she has to turn herself into the most ruthless conqueror there ever was. In essence, she attempts to delete the part of herself that gives her empathy to go full on Ultron so that she can justify her planned genocide pure, cold logic. For someone like her who’s said to genuinely value life, it’s the only way she can bring herself to actually go through with this extreme plan to preserve her people’s existence, leaps of logic be damned.

During the leadup to this, our team of supporting characters verifies their own roles in the plan. Wuk Lamat, Krile, and G’raha Tia all agree to accompany our character to take the fight to Sphene, while Erenville will remain behind to manipulate the systems of the Meso Terminal and Living Memory to bring us more help if needed. Well, it turns out it is needed. Once we face Sphene, she captures each of our allies and forces them out of the system. The only one she keeps is us, because she recognizes we’re too dangerous to just let go. We need to be dealt with here and now, and she plans to use all the power she’s accumulated to do just that. Cue the final Trial, where we use the now well established magic of Azem’s crystal (one of the ancient Ascians, whom it is heavily implied the Warrior of Light is descended from) to summon up our allies and take the fight to Sphene.

At a certain point, she unleashes a gargantuan surge of power to pin us all down so she can prepare to execute us. Now then, given what I’ve discussed so far, would you care to take a guess who shows up to help us?

Is it Krile and G’raha Tia, the latter of which proved himself to be one of the most competent spellcasters alive in this world?

Is it Y’shtola, Thancred, Urianger, and the twins Alphinaud and Alisae, our long time companions from the Scions of the Seventh Dawn, brought in by Erenville to give us much needed support as they have so many times in the past?

Or is Wuk Lamat going to literally break through Sphene’s code with her axe, take a direct hit from her while dealing more damage than any of the players in the party can, and emotionally petition the literal machine that deleted all of her memories of empathy, sympathy, kindness, and all those other things that would’ve made Sphene a decent human being?

Because of course it’s Wukkie Baby.