The Spiritual Battle that Predator Hides in Plain Sight

Billy Sole's conflict with the iconic alien hunter doesn't just foreshadow Dutch's change in character.

Chances are good there isn’t much need for me to link this essay since it’s likely those of you who’d read this have already seen it, but out of a sense of politeness and respect I’m going to do so anyway. Yesterday,

gave us one of the deepest examinations of the 1987 action/sci-fi/horror film Predator that I’ve ever seen. On the off chance you haven’t read it yet, I highly recommend you do so. You can find the essay here.Librarian’s essay is a deeply thought provoking piece, standing as yet another point of evidence that Predator is one of those rare and wonderful experiences that’s more than the sum of its parts. As a piece of 80’s era entertainment, it captures the three most memorable genres of that decade in miniature; featuring high octane action driven by witty warriors who are either lean or muscular, and evolving into a tense sci-fi slasher set in the dense and steamy jungles of South America.

It’s the sort of film that invites you to watch it with a bowl of popcorn, enjoying the spectacle it provides on the surface. However, as it provides that spectacle, it starts whispering things under its breath, waiting to see if you’ll catch on. This layered nature is why I consider it to be one of my favorite films of all time, holding a comfortable spot in my top 10 that I doubt it will ever be shaken free of.

Over the years, I’ve re-watched Predator numerous times. The same goes for its admittedly inferior but still very entertaining sequel, Predator 2, which trades the actual jungles of South America with the concrete jungle of early 90’s L.A. The sequel pits loose-cannon-cop-with-a-mean-streak Mike Harrigan (Danny Glover) against a new one of these alien hunters, affectionately dubbed “the City-Hunter” by Razörfist in his Rageaholic Cinema entry on the movie. Where spectacle is concerned, Predator 2 meets and arguably exceeds its predecessor. Where genuine depth is concerned, no entry in the franchise has ever compared to the original, as evidenced by the various articles and essays, both written and video format, digging into the hidden layers of meaning within the movie.

As you no doubt guessed, Librarian’s essay has inspired me to do just that. It won’t be as robust and broadly scoped as his essay since the topic I’m leaning on is more granular in nature. Even so, my hope is that fans of the film will find these observations I’ve made to at least be interesting, even if they may end up disagreeing with my take.

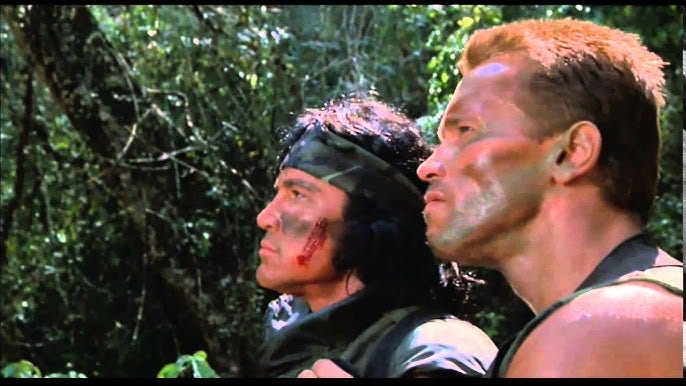

The subject of this essay a a specific member of Dutch’s specialist commando team; Billy Sole, played by the late Sonny Landham1. Billy is the team’s tracker, a skilled survivalist who uses his sharply honed skills to accurately lead the rest of the crew through the jungle of the unnamed South American country they find themselves in. His ability in this regard is put on full display through the first portion of the opening act, blazing a path through the jungle as he follows a trail that leads him to a missing team of savaged Green Berets.

Strung up in the trees, the skinned and eviscerated bodies of their fellow soldiers - one of whom Dutch knew personally - is a gruesome sight that serves to stoke the desire for payback in the team. It’s assumed by some that these men were ambushed and killed by the guerilla fighters in the area, their bodies set out as grim examples to their enemies. Not all are convinced of this, though, least of all Billy, who quickly catches onto numerous discrepancies that go beyond the fact that the valuable equipment those men were carrying had been abandoned with their bodies, something the guerillas would never do.

If you pay close attention to Billy, you’ll notice that he makes a habit of watching the canopy even before they reach the bodies. On their way through the jungle, in another display of his survival skills, Billy chops a vine that he recognizes has drinkable water inside and sips at it. With his head and eyes tilted up, he either sees or hears something that’s out of frame, and slowly begins to scan the canopy above. This is the moment he becomes vaguely aware of the titular Predator, a detail that’s reinforced by the fact that as he begins picking his way through the woods, we hear the creature’s iconic clicking sounds in the seconds before he finds the flayed men.

From here on out, Billy is fully aware that something is out there. He can’t explain what it is, but it’s there, and after it takes the lives of the talkative jokester Hawkins (Shane Black) and the iconic Blaine (Jesse Ventura) during their raid on a nearby guerilla encampment, he’s the first to realize that whatever’s out there, it’s after them. This is soon verified when Sgt. Mac Eliot (Bill Duke) spots the cloaked creature for the first time, and proceeds to begin leveling the swathe of jungle in front of him with Blaine’s minigun. However, it’s important to note that this doesn’t happen until after Dutch and the rest of the team notice that Billy’s been spooked about something.

Honestly, Billy’s awareness of just how wrong the situation is adds significant tension to the middle portion of the film. At this point we know something is out there, but we don’t know what. Even when we get our first glimpse of the Predator, it’s with the creature’s optic camouflage active. All we see is what Mac sees, a vaguely human shape with a flash of yellow eyes. This is the sight that sets him into a panic and makes him unload Blaine’s minigun into the jungle, which Dutch and the rest of his men join in on with their rifles.

After this first sighting, the team is trying to figure out exactly what the hell they’re dealing with. All of them are uneasy, and with good reason. This thing killed two of their own, one of them being the most outwardly macho of their bunch, the sort of badass you would normally expect to survive through to the movie’s end. Now they’ve just leveled a tract of jungle, and what do they have to show for it? A few drops of florescent green blood, a strange howl of pain echoing from somewhere deeper in, and Anna - a female hostage they took from the guerilla camp - repeating eerie lines in Spanish about the jungle having swallowed their friends, which are kindly translated by the team’s resident Latino soldier, Jorge “Poncho” Ramirez (Richard Chaves). By this point, the only one who continues to insist that this must be the work of more guerillas is CIA operative and noted outsider to Dutch’s team, Al Dillon, who’s played to superb effect by Carl Weathers.

It’s at this point that we get what I’d argue is the most important scene in the movie when it comes to fully establishing Billy’s role in it.

“There’s something out there waiting for us, and it ain’t no man. We’re all gonna die.”

Two things are notable about Billy. The first of them we’ve already discussed: the fact he’s the first member of Dutch’s team to realize that the creature is out there, and they’re being hunted. The second is his death. Not long after Billy makes his fears known, the slasher elements of the movie come into play. One by one, the rest of Dutch’s team is picked off by the creature. Mac is the first of them, killed by the jungle hunter when he thinks he’s got the drop on him. Dillon is next, with his death being among the most brutal in the film.

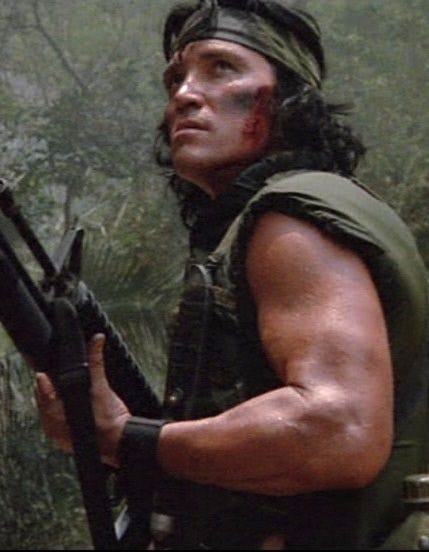

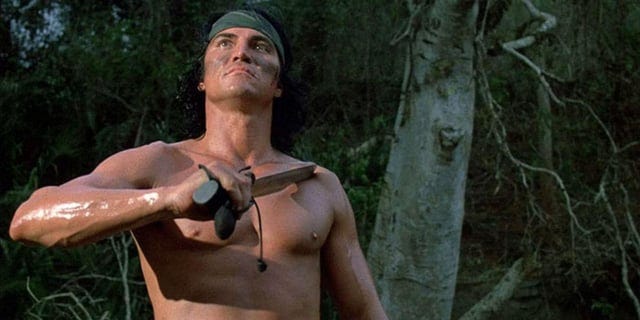

Billy is third in line. However, unlike Hawkins, Blaine, Mac, and Dillon, he’s neither ambushed nor does he attempt to fight the creature from a distance. Instead, we’re given the scene everyone who’s seen the movie remembers him for. As he follows Dutch, Ramirez, and Anna across a fallen tree in their flight through the jungle, he and the others hear Dillon’s death wail. Taking up the rear of the group, Billy throws his rifle away, strips off his vest, and turns around. Then, still watching the canopy, he draws his knife and prepares to fight the monster head on.

This is one of two ways in which Billy’s death differs from those of his counterparts. He’s the first to stand up to the creature directly, eschewing the modern techniques and technology he’s trained with to stand face to face with it as a warrior. He will fight this thing off and kill it with his knife, or he’ll die trying, buying Dutch and the others a few more moments to get away.

The other way his death differs is that he’s the only member of Dutch’s team to be killed off screen. We see Hawkins get cut down and dragged off by the semi-invisible Predator. We see Blaine shot through the back by its shoulder cannon. We see Mac shot through the head by the same weapon, and Dillon’s arm blown off before he’s skewered by the creature’s twin arm blades. We even see Ramirez get shot from off screen, followed by Dutch nearly being killed himself.

Only Billy isn’t shown being killed, but he is shown afterwards, and this choice paints his character in a very unique light.

It’s pretty obvious even on the surface that Billy’s decision to throw away his rifle and fight with his most primitive weapon foreshadows how Dutch will face the creature in the final act of the film. However, there’s another thematic element at play with the way Billy’s character is handled, even after his piercing and, frankly, spine-chilling death wail cuts through the jungle.

Throughout the first act, Billy is shown to be the one who is the most keenly aware of just how wrong the situation the team’s thrust into really is. There are far too many discrepancies in what he’s seeing, too many unfamiliar elements that don’t make sense and can’t be explained even with his extensive knowledge. Because of this, he’s constantly watching the canopy, constantly on edge, constantly on the lookout for the wrong in their midst. When they initially find that wrong in the form of the Predator, he’s the first to comprehend that whatever this thing is, it’s beyond anything they know. An entity they can’t understand is hunting them, and he knows it’s going to kill them.

Billy’s actions and characterizations hint to a form of reverence for the environment around them. As their master scout, he’s intimately familiar with dense and dangerous natural settings like the one he finds himself in. The film does a fine job of conveying this knowledge without telling it to us outright, too. So it is that when he becomes spooked, so too do the rest of Dutch’s team, and so do we, the viewing audience. It indicates a subtle sort of spiritualism in his character, one that carries into the final act of the film when Dutch confronts the Predator himself. Librarian’s essay explores this from the approach of the threat the creature poses to the masculinity of the film’s men. There’s truth in this, and it helped me to see why Billy’s death, which a younger me found the most disappointing, is now the one I find the most harrowing.

I don’t know whether this was intended by director John McTiernan or the Thomas brothers who wrote the film. Frankly, I don’t know if any of the layering that has since been discovered in the movie was intentional. Yet whether intended or not, I’m of the opinion that the handling of Billy’s character hints at an underlying spiritual conflict within the movie. Billy, and later Dutch, represents an irreducible form of man: a survivalist warrior, one with nature and the surrounding world, willing to kill and die for his tribe and his values. They are the archetypal warrior, men who should stand in service to nation and kin. Of course, their relationships to nation are more complex than this, given it was the 1980’s, but the point is still clear.

They are men, they are warriors, and a warrior’s job is to protect what he loves and values against the monsters that would destroy them.

The Predator is such a monster, a half-visible demon from a realm beyond our own. Now it’s not a literal demon, but the role it fills in the narrative is much the same. It’s an entity which exists to destroy, killing for no other reason than sport. These men, these warriors, are its prey, and their skulls and spines the trophies it wishes to claim.

On a narrative level, I believe the off screen killing of Billy has a strong metaphorical significance which is sold to us by what’s done to his body. After the rest of his team is killed and Anna flees to the pickup site2, the Predator tries and fails to find Dutch when the cold mud that cakes his body after he leaps off a waterfall masks him from the creature’s infrared vision. This begins the montage where Dutch prepares to face the Predator in the same way Billy did, as the irreducible archetype of the warrior.

However, while he sets traps, fashions himself a bow, and turns his knife into a spear, the jungle hunter is busy claiming and cleaning his trophies by ripping spines and skulls alike out of the corpses of his victims. And who’s body is it that we see him desecrate?

Billy’s.

I take the desecration of Billy’s corpse to represent the spiritual disdain held for men like him. To this otherworldly demon, the body, mind, and soul of these people are nothing. Only their skulls matter, and even then only if they provide him with sufficient challenge to entertain him. However, as the only one to stand up to him in direct challenge, Billy must be made an example of in the narrative sense. This is done to push home a couple points. Firstly, the one which Librarian focuses on in his story; that the time of these sorts of men is gone, and they will die in the face of the forces that seek to crush them on all sides. Dutch’s defeat of the Predator offers a glimmer of hope in this sense, but the harrowed expression he carries at the film’s end shows that it’s a faint glimmer.

The other point is more spiritual in its nature, though it could certainly be argued that both of these are spiritual points. Billy is a man who dared to face the monster directly but failed to slay it. His willingness to do this is the greatest showcase of courage the film as seen yet, at least until Dutch does battle with the fiend. Billy knows he’s likely going to die in this fight, but he faces this enemy anyway, ready to lay down his life for the chance to kill the beast and help his remaining two friends escape. There’s also likely an element of revenge in it, given the Predator killed Mac, who’s shown to be particularly close with Billy.

Desecration, in this case via the violating of his corpse, is one of the most severe forms of disrespect that exists. Even as a nonreligious man I recognize this fact. While the Predator can be argued to be showing a certain degree of respect through his trophy gathering, this overlooks what he’s done and is doing to retrieve those. Human lives, which is to say our lives, mean nothing to the monster save a chance at sport. The sanctity of our bodies matters not a whit to him, so he has no issues with ripping out our spines and vacuuming the meat and blood from our skulls. By the same vein, per the film’s first act, he has no issues with discarding the flayed bodies of those who presumably failed to impress him. This can be assumed of the Green Berets because they all still have their heads. It seems more like their bodies were used to try and stir up fear in the other people, likely in hopes of drawing out worthy prey.

Billy, and indeed everyone in Dutch’s team, is shown to be a man in peak physical condition. His body is strong, fashioned that way from a life of training and fighting. It exemplifies the idea of our bodies being our temples. Thus, for the jungle hunter to steal his corpse and tear out his spine on screen is a metaphorical desecration of his human temple. Save for the ways in which we can be made to serve their desires, we mean nothing to the monstrous and demonic.

It’s for this reason that I think Predator isn’t just a battle for survival, or a simple monster movie, or even an examination of the deeper struggle of strong men against a society that views them less as people to be lauded for their strengths and convictions, but more as assets to be used up until they’re extinguished and discarded. It’s also an ages old spiritual struggle, man’s unending battle against the otherworldly forces that would see him destroyed for no other reason than sating their appetites.

Or maybe I’m just reading too much into it.

I won’t bother listing who Dutch is played by. At this point, even those who haven’t seen the movie know Dutch is one of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s most iconic roles.

The result of the oft joked at “Get to the choppah!” scene.

Billy's willingness to drop his weapon and stand his ground only with a primitive knife is a defining moment in the film. It shows that man is not made to kill by gun alone. Most of the other warriors in the band are known by their high-tech and explosive weapons: Blaine (Minigun), Mac (giant M60E3 machine gun), Dillon (iconic MP5 from Goldeneye), Pancho (Multiple grenade launcher). I had to look it up, but only Billy and Dutch wield the somewhat simple SP1 rifles (an early version of the AR-15 rifles). They are not dependent on the technology in the same way, and both seem like they could enter into the jungle without arms and survive.

The other men seem to have chips on their shoulders and are skittish, while Billy and Dutch exude that masculine steady energy and reflectiveness. I think the film shows man's ascendency from mere existence and to answer the call for a higher, spiritual battle against enemies without form. There are elements of spiritual warfare here against unseen foes that only Billy as the Native American Scout and Dutch as the true spiritual leader (as opposed to the "assigned leader" Dillon). This message is brought home with the sound of Billy's last name: Sole (Soul). Great essay, man!

The original Predator is definitely in my top 10 all-time and is one of those rare movies that you can watch over and over again. My favorite all-time movie is the original Blade Runner, but in terms of re-watching, Predator might be number one.