Here Come the Rats - A Review of Fritz Leiber's "The Swords of Lankhmar"

After reading his first four Lankhmar books across the summer, Leiber's fifth represents a pinnacle within the series.

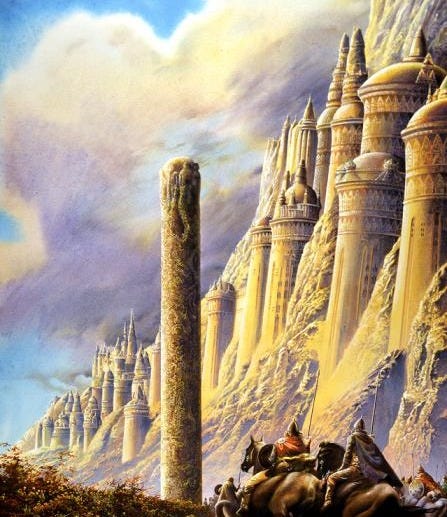

Permit me to fashion an image in your mind. Imagine yourself on the deck of an old galleon. The day is warm and bright, but misty. Massive canvas sails, held aloft on spire-like masts, bulge in the wind and carry you onward at a steady pace. You are among the crew, cleaning the deck or otherwise manning your station. Perhaps you’re spotting in the crow’s nest, or maybe you’re down in the hold keeping watch over the grain shipment being hauled on your ship. And not just your ship, for yours is but one of a small fleet of such trade vessels.

Normally hauling grain like this wouldn’t be cause for overmuch concern. Yes, piracy is an issue, but the fleet you’re part of is royally sanctioned and well defended. Pirates would have one hell of a time picking your ship off, although, the fleet is unusually widespread today. Nervous chatter lingers on the deck partly for that reason, but it’s not pirates on the lips of the sailors. It’s rats.

No sailor appreciates these vermin, and sailors hired to transport foodstuffs like them even less than the rest. That grain in the hold is what guarantees your pay, and that’s reason enough for you to hate those invasive little beasts. Yet that’s not the worry your shipmates discuss. Nay, it’s a more superstitious fear - rumors of the little vermin sinking ships not at all unlike yours. Sailors are a naturally superstitious lot, of course, and who can really blame them when they spend so much of their time away from land and at the mercy of the ocean?

Even so, their talk makes your skin crawl, especially considering that strange Lankhmarese dame, the daughter of the merchant noble who’s grain you’re shipping, was made to sail with you. Women are bad luck on the seas. Their fickle nature makes them dangerous, every sailor knows that. No wonder the others are so ill at ease, especially considering there’s two of them - the noble dame, and her handmaid. Yet even this shouldn’t be enough to have the men as high strung as they are. There must be something more to it. And that’s when you learn that the noble dame brought eleven pets with her.

Eleven white rats.

This is essentially the scenario that The Swords of Lankhmar thrusts the reader into; as well as our larcenous central characters Fafhrd, the copper haired northern barbarian trained in the ways of skaldic poetry, and the witty and wily sorcerer-thief the Gray Mouser. What follows from this setup is, at least so far, what I would consider to be the finest adventure that Fritz Leiber has yet sent his pair of dashing rogues out on.

In my previous review on the Lankhmar series, I made note of the fact that these stories aren’t novels in the traditional sense. Leiber initially wrote the exploits of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser chiefly as short stories and novelettes in serialized format. The seven Lankhmar books feature this collection in chronological order. Generally speaking, you can tell that these stories weren’t originally written with the intent of being put together to present typical single novels within a greater series. This is one of the ways in which The Swords of Lankhmar stands out as something exceptional compared to the prior four books.

Now I want to be perfectly clear, this isn’t to say that The Swords of Lankhmar reads like a traditional novel. The particular hallmarks of Leiber’s short-form writings are still present here. While this book follows a more traditional chapter-based format, unlike the previous ones where the “chapters” were clearly delineated as their own stories within the overarching narrative of that particular book, readers will still notice that the story is separated into distinct sections. The first act takes place on the merchant ship I mentioned in my intro. The second act alternates between the Gray Mouser investigating a conspiracy in Lankhmar while Fafhrd, having ended up separated from him by many miles, rides back to the city with haste.

The third act will remain a mystery. If you wish to know it, you’ll simply have to read the book.

I already established in my previous review that I find the Lankhmar series to be both well written and exciting. Leiber has a particular style to his prose that borders on the poetic, and his ability to weave the fantastic and the whimsical alongside the brutality the Sword & Sorcery genre is often known for is, in my mind, delightful. As such, it should come as no surprise to learn that this tradition continues throughout The Swords of Lankhmar. And yet, it did surprise me, because he doesn’t merely continue his stylistic tradition. Leiber actively improves upon it in this book.

Where the story itself is concerned, I found The Swords of Lankhmar to be fairly simple and very solid. Subterfuge, superstition, and intrigue all play their roles in this story, but it’s not very difficult to figure out the course Leiber’s plotting. However, familiar though this type of story may be, this ends up working to the author’s benefit because it leaves him room to elevate these simple ideas in ways that are creative, engaging, and most of all, just plain fun.

More than the previous four books in the series, with exclusions made for the times when the bizarre patron sorcerers of our larcenous heroes - Ningauble of the Seven Eyes for Fafhrd, Sheelba of the Eyeless Face for the Gray Mouser - arrive on the scene, The Swords of Lankhmar leans into the fantastical side of its chosen genre. Each story within the series so far is unarguably fantasy, but The Swords of Lankhmar raises the bar in such a way that as I read it, I found myself reminded of other fantasy authors I’ve read in the best sort of way.

For example, while Fafhrd and Mouser are aboard the merchant vessel in the first act of the story - they were placed there as hired guards to protect Hisven, the noble dame who keeps those eleven trained rats - they have an encounter with a strange traveler. After catching the sound of a strange whooping on the ocean breeze, which the sailors claim is the mating call of a type of sea dragon, the ever boisterous and adventure hungry Fafhrd begins imitating the call. Sure enough, it turns out the sailors were right, and a multi-headed serpentine dragon emerges from the morning mist! Its colorful heads, bright with red and green and purple scales, loom over them as if seeking out food and the men fear they’ll be made a snack of!

However, much to the surprise of all, it turns out the beast is being ridden by an odd man in jet black armor. The stranger speaks a language they’ve never heard before, but Leiber does us the kindness of revealing that it’s not just any alien tongue. This man is speaking German, of all things, and is a traveler from a future version of our own world into Nehwon, the world in which the Lankhmar stories take place. The idea of otherworld travelers isn’t new to the series at this point, as the third book features an adventure wherein Fafhrd and Mouser both end up in our own world during the pre-Renaissance. Which is to say, it’s not quite the depths of the Dark Ages, but the Renaissance isn’t in full swing yet, either.

If you’ve read any of my previous articles on dark fantasy, or even some of my musings on writers and writing and why we do what we do, you’re likely already aware of my thorough enjoyment of Michael Moorcock’s fiction. The saga of Elric of Melniboné is one I’ve hailed as a particular favorite of mine, a series which catapulted itself onto a high pedestal and quickly became influential to me in spite of it being a rather recent discovery in my life. The encounter Leiber describes with this strange German man and the hydra-like beast he rides felt just like the sort of fantastical event I came to expect from Moorcock’s writing, yet not once did I feel as though Leiber was ripping off or plagiarizing his contemporary, as the style and setup of the event were still distinctly Leiber’s. Instead, it felt more like friendly homage, though I’m unaware as to whether or not Leiber and Moorcock had any kind of friendly or working relationship.

Nevertheless, it came as a pleasant surprise to me to have that feeling evoked, and it served to further fuel my excitement and my hunger to continue the story1. Similarly, later events in the story, as well as a plethora of concepts and ideas which Leiber plays around with in this book, reminded me of a later fantasy author who captures the imaginative nature of the genre in a way that many would struggle to replicate. I speak in this case of Michael Ende, author of The Neverending Story. Now I’m not about to say that The Swords of Lankhmar gets as wildly fantastical as the aptly named land of Fantastica does, but there are a number of elements within this story that reminded me of the particular way that Ende blends adventure and fantasy together in his story. By the by, if you only know The Neverending Story from the movie, do yourself a favor and read the book. It’s wonderful fiction, and I plan to reread it early next year in preparation of a future review.

All this being said, this story wouldn’t have reached the heights it did on the backs of predictable intrigue and imaginative fantasy elements alone. A strong cast of characters is needed to give those elements the weight they need and deserve, and once again, Leiber delivers. I already spoke at length about why Fafhrd and Mouser make for an engaging leading duo in my prior review. Everything I said then remains true here, too. However, I also mentioned the following in that review when it came to speaking of the “Lankhmar wenches,” as the supporting females in this story are sometimes referred to:

Speaking of maidens, this is one of the areas where Leiber’s writing is on the weaker side. For as fantastic as Fafhrd and Mouser’s characters are, the various love interests or femme fatales they encounter across their stories are far less consistent in terms of their quality. At my current point in the series, with four of the seven books finished, the two best female leads the pair have encountered thus far are their original two love interests. For Fafhrd, it’s the dancer Vlana, who’s exotic wiles and determined nature lure him away from his tribe and the woman he was originally set to marry. For Mouser, it’s Ivrian, the meek daughter of a cruel Duke who reigned over the land where he was studying magic under a hermit wizard named Glavus Rho. These women are ultimately responsible for both boys starting on their adventures, and they’re also responsible for shaping the men they would eventually become. How and why I won’t say here, for it’s best read.

Unfortunately, future female characters often aren’t as interesting as Vlana and Ivrian were. Most of the time they exist only for the specific stories they’re presented in, meant to fill specific roles for the plot more than to act as characters in their own right. There are a couple exceptions to this, though, such as the pair of clever black market fences each man encounters in “The Two Best Thieves in Lankhmar,” the third story of the fourth Lankhmar book, Swords Against Wizardry. I won’t spoil the events of the story here, as to do so would require me spoiling the two stories that take place before it, so let it suffice for me to say that this pair prove to be wonderfully clever foils for our main characters who were expertly utilized within this specific story. Hopefully we’ll see more examples like this, or better yet more female characters with the depth of Vlana and Ivrian, going forward.

The Swords of Lankhmar breaks this unfortunate trend, and that’s chiefly due to the inclusion of a clever and wily young woman who quickly catches the Mouser’s eye, and very nearly captures his heard. I’m sure it’s of little surprise that I speak of the noble dame I mentioned at the beginning of this review, Hisven. Hisven and her handmaid, Frix, are easily the two best realized supporting females that Leiber’s developed since Vlana and Ivrian. Playful and fiercely intelligent each in their own ways, their characters not only play well off each other, but off Fafhrd and especially the Gray Mouser. Discussions between Mouser and Hisven quickly become playful battles of wits, and their interactions are among the most enjoyable not just in this book, but the entire series so far.

Hisven and Frix aren’t the only new women to join the fray. Though their parts aren’t as significant and so they’re not quite as fleshed out, both Fafhrd and Mouser meet some unique ladies that further support their individual stories within this greater tale. For Fafhrd, that character is Kreeshkra, a ghoul woman who’s bizarre appearance - her translucent skin leaves her bones visible through it - at first horrifies, then fascinates him the more he comes to know her and her strange customs and ideals.

In Mouser’s case, the two he meets are directly tied with the patron who initially worked to have those merchant ships sent out, Lankhmar’s immature and casually cruel beanpole of a Lord, Glipkerio Kistomerces. Touching on him briefly before moving to the two named women in his service, Glipkerio is the current leader of Lankhmar. Painted throughout as thoroughly vain, immature, and casually cruel as previously mentioned, his is the sort of character that you quickly love to hate, the sort of scuzzy weasel that makes your skin crawl with his haughty mien and his undeserved sense of superiority.

In his service are two named women of import. The first is Elakeria, a servant girl who finds herself smitten with the Mouser. Of the female cast in this book, I’d argue she’s the one with the least depth. However, that’s not to say she isn’t enjoyable to read about. It’s simply that she falls more in line with the previous “Lankhmar wenches” we’ve seen in books 2 through 4. Effectively a slave to Glipkerio in all but name, Elakeria gives us a closer view of the effects of his casual cruelties and his bizarre proclivities. For one thing, because of the fact that he’s such an oversensitive little fop, Glipkerio has her - and in fact, all of his servants - shaved completely bald from head to toe. She isn’t permitted to grow even a single body hair. Further adding to this indignity is the fact that she’s kept slim and forced to parade around in the nude, as again, all his servants are.

The only exception to this rule is the house matron. I honestly can’t recall if that’s the correct title she’s given in the book, but the character of Samander acts as both the enforcer of Glipkerio’s rules among the servants, and as his nanny. A callous and corpulent woman, so foul in her appearance and demeanor that she’s described as not only being horribly overweight but bearing a patchy mustache that she carries with undue pride, her relationship with Glipkerio is just plain creepy. I won’t get into the details here, but suffice it to say that she’s a vicious taskmistress, and that later scenes in the book reveal the part she had to play in Glipkerio developing his tendencies of casual cruelty.

A few other characters exist to round out the cast, with Hisven’s father, Hisvet, being among the most notable of them. However, I’m not going to touch on him or on the other characters allied with him, as doing so would require me to spoil much of the book and I think that would be a damn shame.

In all, it’s safe to say that I absolutely loved this book. The stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser were already exciting to me in a way that made many of the usual tropes of Sword & Sorcery feel fresh again. The touch of humor and whimsy that Leiber brings to these tales lifts them up from those more inclined to imitate the more brutal elements found in the works of writers like Howard and Moorcock, while leaving out the more thoughtful and reflective elements of those authors. Like a good chef, Leiber takes the ingredients we’re familiar with and elevates them into something greater, and The Swords of Lankhmar reads like the culmination of all he’s learned and developed so far, which is particularly interesting to me since while it’s chronologically the fifth in the series, it was one of the first three volumes released in 1968. That said, the stories which comprise this volume were written around the midpoint of Leiber’s career.

I don’t feel it’s wrong of me to say that the following two volumes in the series, Swords and Ice Magic (1977) and The Knight and Knave of Swords (1988) have some large shoes to fill. The standard for the exploits of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser have been consistently high throughout my reading of the series, but The Swords of Lankhmar raised the bar for me. It’s my hope that Leiber can clear that bar with the next two books, but even if he can’t, I’m confident his high standard of quality will continue.

Avoid It | Discount Bin | Tough Sell | Flawed Fun | Great Read | Must Own

As a note, I actually finished this story midway through October, just a couple weeks after I finished The Last of the Mohicans. Life being what it is, though, I haven’t been able to take the time to sit down and review it until now.

Isn’t it Hisvet and Hisvin? And Reetha (not Elakeria)?

Glory to the rodents! With or without big laser rifles :D