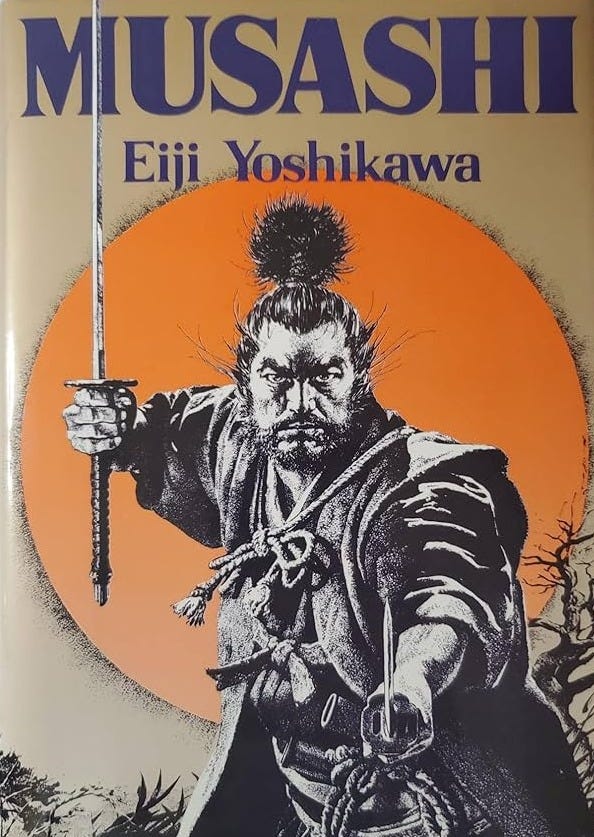

From Sekigahara to Himeji - Reviewing Eiji Yoshikawa's "Musashi"; Book I: Earth

Even so early in my journey through this book, the influences of Eiji Yoshikawa's world renown novelization of the legendary samurai's life remain easy to find.

When sharing my previous book review, where I covered The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimoore Cooper, I made mention of the fact that I’d recently begun compiling a goodly amount of classic fiction to read. I began this journey with Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger. Known to be the last story he’d ever written before his passing, the history behind the posthumous release of this darkly existential tale, which I touch on here, is every bit as interesting as the story itself. Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is another book I’ve had waiting in the wings for some time, and is likely to be the next classic I move onto.

However, the book which currently holds my attention comes from across the pacific, out of the always captivating Land of the Rising Sun. I speak, of course, of Eiji Yoshikawa’s famous novelization of the life of the man who is arguably Japan’s most legendary samurai, Miyamoto Musashi.

If you’re someone who’s taken an interest in Japanese history, or even if you simply happen to be a fan of the island nation’s popular media, chances are very good that you’ve at least heard this famous name before. The life of the real world Musashi is one that’s been widely researched, while the man’s incredible deeds have led to him being fictionalized and reimagined not just across popular Japanese culture, but pop culture worldwide. In fact, as I read through a couple more chapters this morning, I was struck with the realization that as I’ve been reading the book, I’ve also been watching a show that’s drawn some direct influences from both Yoshikawa’s novelization and Musashi’s life. The show in question is Blue Eye Samurai, a brutally action packed animated drama released on Netflix just shy of a year ago at the time of this writing.

By the way, if you’re the type who enjoys a good blend of character driven drama and action spectacle, give Blue Eye Samurai a watch if you haven’t already.

I fully expect this isn’t going to be the only example which I’ll eventually realize was influenced by Eiji Yoshikawa’s novel. Musashi has been considered a classic not just among the Japanese people, but all across the world for over four decades. Originally written in serialized format and released in newsprint1 in the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun from 1935 to 1939, Yoshikawa’s writings were finally compiled and published in book format in 1971. A decade later, Musashi was translated into English and released to the West.

Yoshikawa’s novelization breaks Musashi’s story up into seven “books” which follows a different stage of the swordsman’s life. This review will be focused on the first of these, which is titled, “Book I: Earth”. Do note that these aren’t actually physically separate books within a greater series, and are probably best thought of as story arcs akin to the acts in a play.

As mentioned, Book I: Earth details the earliest stages of Musashi’s quest to master the way of the samurai. Beginning in the aftermath of the battle of Sekigahara, the story opens not on a soon-to-be-renown samurai in the midst of his quest, but on the boy who would one day become that man, Shimmen Takezō. A seventeen year old glory hound, Takezō and his friend, Hon’iden Matahachi, both signed up to serve in the forces led by Ishida Mitsunari.

Unfortunately, this places both young men on the losing side of the battle. Awakening in a field of bodies, an injured Takezō is found by Matahachi and the two begin their efforts to sneak past the patrols of soldiers under the newly established Tokugawa Shogunate. During this escape attempt, Takezō soon finds himself growing weary and sick from his injury and a lack of food.

This is where the first stage of Takezō’s journey of growth begins. Currently, his singular goal is to return to their home village of Miyamoto. As you can surely guess, this is where he derives his new surname from when he eventually changes his name to Musashi. As I’m sure you can also guess, Takezō’s injury makes it all but impossible for he and Matahachi to make the long journey home. Thus, in need of time to heal, they end up taking shelter in the home of an older woman named Oko and her daughter, Akemi.

It’s at this point that we really begin to see the character of these two young men. Akemi is a sweet and innocent girl, arguably more so than she should be given the damage the battle has caused to their region and the fact that she’s almost a full grown woman despite her youthful appearance. Her mother, however, proves to be lascivious and manipulative; a vain woman far more interested in feeding her expensive tastes and clinging to her youth. This dynamic puts a strain on Takezō and Matahachi in different ways, leading the latter to become reckless while the former is recovering in hiding.

Through the events of the first two chapters of Book I: Earth, we’re given a look not just at the values of these two young men, but their immaturity. While Takezō is shown to arguably have a better head on his shoulders than Matahachi, it’s also made clear that he’s brash and impulsive, which ends up making trouble for Akemi and Oko. This isn’t to say that the women are innocent in this matter, though Akemi is by far the one least at fault for the problems that come their way. Even so, all have their part to play in Oko and Akemi ultimately being forced to leave their home, which leads to Matahachi and Takezō parting ways, too. Immature young man that he is, Matahachi has allowed himself to be taken in by Oko’s wiles, even though he’s already engaged to be married to a young woman back home.

I focus on these two chapters for two reasons. Firstly, as the jumping-off point for this story, they do a lot of the legwork in establishing who these young men are at this stage in their lives. Takezō and Matahachi may each be seventeen, old enough that they should be considered men by now, but their attitudes and behaviors paint each of them as immature boys who still have a great deal of learning to do. Each of them desires to be a great samurai, but by the end of Book I, both are shown to lack vital understanding of not just what it is to be a samurai, but what it is to be a man and, on a conceptual level, what it means to be human.

These are the lessons that Takezō must begin to learn through the course of this first arc, and it’s only once he returns to Miyamoto and suffers a great deal of strife that he begins to learn them. You see, as someone who fought on the losing side of the war, the laws of the time effectively state that Takezō is to be captured, imprisoned, and likely executed as an enemy of the current Shogunate. His hope is that by returning home, he can find a way to fit back into his old life through the help of the people he grew up with. Problem is, Takezō isn’t well liked among the people of Miyamoto.

Actually, that’s an understatement. Because of the boorish bully he was when he was younger, fed into by the fact that he’s always been large for his age and had a chip on his shoulder for being made to live under the strict watch of his father, he’s both hated and feared by many people in the area. Seemingly the sole exception to this is a young woman named Otsu, an orphan who was raised by the priest of the local temple and acts as his assistant. It also happens that she’s the young woman to whom Matahachi was engaged, the one whom he abandoned in favor of the vain Oko.

We learn that of the people in Miyamoto, Otsu is one of a select few who still holds out hope that Takezō and Matahachi survived the war. The other who holds out this hope is the matron of the Hon’iden family, Matahachi’s overbearing and extremely willful mother, Osugi. Unlike the far more reasonable Otsu, though, she places all the blame for Matahachi marching to war on the shoulders of Takezō, unable to accept that her son isn’t the perfect young man she believes him to be.

I accept that this is a bit abrupt, but this brings me to the second reason I specifically focused on the first two chapters of Book I above the rest - the density of the story. In terms of length, this first arc of Musashi is about as long as Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger. That is to say, it’s on the shorter end of things. Yet in this act alone we meet about eight characters that have moderate to significant impact on the story, not including Musashi himself. We see the way Takezō struggles before he takes his new name, how his choices impact the people around him, how their choices impact each other, and then how they end up affecting Takezō. With so much story neatly packed into such a small space, it would be near impossible for me to pull at too many more of these threads without spoiling most of this first act, which I’m loathe to do.

As such, I’m going to pivot my focus to the character that’s arguably the single most important one in this arc: the eccentric Buddhist monk, Takuan.

Apart from just being a joy to read due to the levity he tends to bring the story, Takuan acts as a driving force of change within this act. It’s through him that Takezō is eventually able to become Musashim begin his lifelong quest to master the way of the samurai, and grow to understand not only what it means to be a man, but what it means to be human. Takuan also provides us a lens through which we’re able to digest some of the ideals of feudal Japanese culture, chiefly Zen Buddhism and their concepts of what it is that makes someone human.

To say that Takuan is an interesting character is an understatement. Not only does he provide the aforementioned levity, the fact that he’s also able to act as a grounding force within the story is remarkably impressive. Yoshikawa’s handling of his character is such that these seemingly contradictory roles feel completely believable. As a result, the mark Takuan leaves on this story is indelible, though it isn’t perfect.

I don’t have much in the way of complaints for this first act. The characters have been engaging and rich. The pacing of the arc incredibly strong with how much substance is fit into such a small space. The story itself has been exciting, tense, and dramatic; all elements which point to Yoshikawa’s fantastic writing2. However, I did find one point at which the story fell a bit short for me, and I hate to say it because I thoroughly enjoy the character, but it has to do with Takuan.

I’m not going to go deep into specifics. As I hinted above, I don’t want to spoil too much of this story because it’s been largely excellent so far. However, about 75% of the way through Book I, we reach a point in which Takuan has managed to find the elusive Takezō, who’s been hiding out from the Shogunate’s samurai who’ve been searching the area for him. What results is a rather harsh punishment for the young man, which makes plenty of sense within the confines of the story. However, what didn’t make much sense to me was a point in which Takuan, during an argument with Otsu regarding Takezō’s treatment, admits that he actively enjoys seeing people suffer in manners similar to what Takezō’s punishment is doing to him.

This stuck out to me in a way that I can’t say was welcome. Takuan isn’t shown to be the nicest person around. It’s made clear quite early on that he enjoys employing his wit and words against people to get under their skin, that he finds it enjoyable to cow people who aren’t as sharp as he is. However, it was never shown to us that he actively enjoyed watching people suffer. As such, Yoshikawa’s choice to have Takuan openly admit this to Otsu doesn’t feel in line with his character. Instead, the revelation comes off as a plot convenience from Yoshikawa, reading as his way of giving Otsu enough of a shock that she’d feel justified in taking the actions she does that progress the story.

That being said, the very fact that this is the sole complaint I had about this first arc does speak very strongly to the quality of Yoshikawa’s writing. I can also say that despite my dislike of this particular choice, it has done nothing to hamper the continued enjoyment I’ve been finding in Musashi so far. I’m excited to see how the story will evolve going forward, and I’ll certainly be reviewing the remaining six books as I complete them. For now, let me simply say that as the opening act to this dramatization of Miyamoto Musashi’s life, Book I: Earth gripped my attention firmly and left me feeling both thrilled and enthralled.

In short, it’s a fantastic opening act.

Take note, fellow fiction writers of Substack. The serializing of our work is hardly unusual, and could be argued to be the continuation of a storied tradition.

So far, this trend has continued on into Book 2, which will receive its own review once I’ve finished reading it.

I have just ordered Musashi: Book 1 on the strength of you review. Thank you.

Some years ago, I saw a documentary on the History Channel, which claimed that Yoshikawa’s novel was an apologetic for Japanese militarism. I didn’t find that to be true at all - if anything, the samurai are frequently portrayed in a negative light.