Clint Eastwood's "Pale Rider" - A Tale of Faith, Retribution, and True American Mythmaking

While "Unforgiven" still stands undisputed as Eastwood's finest Western, "Pale Rider" captures the spirit of the genre in a way few other films have.

Let’s get this out of the way now. I adore Pale Rider.

I stand in agreement with most that Unforgiven is the finest contribution Clint Eastwood made to the genre, presenting a heavily nuanced story which beautifully showcases the often grim realities behind the romanticization we, as humans, love to partake in. Be honest, how many among us have fantasized about living in a different time? From the Western Territories of the U.S. where our classic stories of cowboys with gumption, gritty gunslingers, wily Injuns, smooth Caballeros, and dastardly brigands sprout from; to the churning seas of the Caribbean in the Age of Sail; to the legends of knights and damsels, kings and queens, wizards and dragons which came to us from the Middle Ages; as well as numerous tales further beyond even these in terms of place and time; you’d be hard pressed to find any man or woman who hasn’t indulged in romantic thoughts about how nice it would be to live in such times.

Unforgiven took these romantic notions of the Old West given to us by the Western genre, and carefully cracks it open to give us a multifaceted glimpse at many of the harsher realities of life in this time. The men praised as legends and heroes are often anything but. Living off the land means a life of constant work, sometimes with little to no payoff, which can realistically mean your death if things go poorly. Famous lawmen, bandits, and gunfighters are thought of as celebrities, causing people to forget that the reality of their actions means they’re killers above all else.

Yes, there’s no question that Unforgiven is a stupendous movie, and made all the better if you’ve seen the Dollars Trilogy by Sergio Leone, the famed Spaghetti Westerns that gave Eastwood his break in the genre. Unforgiven is a movie that carefully removes the outer layers of romance to reveal glimpses at some of the grim realities beneath, but in a way that lovingly deconstructs the genre, rather than destroying it. So yes, as stated earlier, I stand in agreement that it’s Eastwood’s finest contribution to the genre. However, it’s not my favorite of his contributions.

That title goes to Pale Rider.

Similarly to Unforgiven, Pale Rider is a film which does away with some of the romance surrounding the Western genre. It’s a film which follows a mysterious character who never gives his name, a clear nod back to The Man With No Name from the Dollars Trilogy. As with the Dollars Trilogy, this mysterious stranger is a skilled gunfighter and a man with great presence. He’s the one we’d expect to follow closest, to be the main character. He’s the one we anticipate is going to mete out bloody justice against all enemies in his path.

Yet his justice isn’t bloody, and he doesn’t seek to start fights in the same way The Man With No Name often did. He arguably isn’t even the main character of the film. Instead, that role is shared by two people: the young teen girl Meghan Wheeler, and the man who’s been helping care for her and her mother, Hull Barret.

I’m getting a bit ahead of myself, though. Before exploring the characters we ought to explore the kind of film Pale Rider is, and the best way to begin doing that is to take a glimpse at its plot. Set in and around the fictional mining town of LaHood, so named for the gold mining magnate who founded the town, Coy LaHood, the film takes place in the fictional California county of Carbon Valley.

As you might guess, this is a Gold Rush era movie, showcasing a slice of the hard life prospective miners and their families led in this time. However, while the town of LaHood is central to the events of the movie, the people living in it aren’t the focus. Instead, our main focus is a community of “tin-panners” as the movie calls them, independent prospectors who use traditional methods of digging, rock breaking, and gold panning to find the ore that’s necessary for building their new lives. Living in the small, unnamed town they built around their claim in Carbon Canyon, this community finds themselves the target of highly aggressive intimidation attempts by the LaHood Mining Company, who seek to drive them out so they can sweep in and take the claim for themselves.

The movie opens on one such intimidation attempt. LaHood’s men, mounted and armed, barrel through the makeshift prospecting town. They trample the prospectors’ gear, bowl the down on their horses, and strike fear into them by firing at their feet and gunning down any pack animals or livestock they find. It’s also during this raid that we’re first introduced to Meghan Wheeler, her mother Sarah, and Hull Barret, who’s been helping to care for them both after Sarah’s husband ran out on them years prior. Meghan, through the panic, is trying to find her dog, while Hull does what little he can to stop the men. His efforts are unsuccessful, for courageous though he is, Hull’s but one man against many, and the strength of his principles alone isn’t going to be enough to dissuade LaHood.

In the wake of this raid, which we learn is far from the first they’ve experienced, Hull runs into members of their community who are leaving. They’ve had enough of LaHood’s men and see no hope in trying to maintain their claim. This is a community on the verge of breaking, and it seems like Hull’s the only one left who’s willing to stand up.

However, there is one other who’s willing to stand at Hull’s side: Meghan. Grief stricken by the fact one of LaHood’s men ruthlessly shot and killed her dog during the raid, she takes a very different tack from the prospectors who are thinking of giving up. After laying her pet to rest, she begins to pray not just for the animal, but for all the prospectors in Carbon Canyon:

“‘The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.’ But I do want!

‘He leadeth me beside still waters. He restoreth my soul.’ But they killed my dog.

‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of Death, I shall fear no evil.’ But I am afraid!

‘Thou art with me. Thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me.’ We need a miracle.

‘Thy loving kindness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life.’ If you exist.

‘And I shall dwell in the House of the Lord forever.’ But I’d like to get more of this life first! If you don’t help us, we’re all gonna die. Please, just one miracle? Amen.”

It’s during this prayer that we get our very first glimpse of the mysterious stranger played by Clint Eastwood, seen riding through distant mountains toward LaHood town. The idea at play here is clear: this stranger is their last salvation, their chance at the miracle Meghan prays for, and it’s not long before we’re shown what he’s capable of. After having their camp ravaged, Hull decides to take his wagon into town. As he’s leaving he’s met by the Conway boys, the sons of Spider Conway, a gruff and irritable prospector who we later learn used to work for LaHood and his son before he had a falling out with them. Both ask Hull where he’s going, and when he answers he’s headed into town for supplies, both essentially say that “seems kinda dumb after what happened the last time.”

All of these interactions take place within the first fifteen minutes or so of the movie, and they do a great job of setting up just how dire the prospectors’ situation is. They truly are a community on the brink, desperately struggling to work their legal claim in the face of ever increasing odds against them. By the same token, it also gives us an idea how desperate LaHood and his son, Josh, are. This rapid escalation hints that there’s reasons beyond simply wanting to mine the land themselves that pushed them to these extreme measures, and we do get that reason revealed when Coy LaHood enters the movie proper about a third of the way into the runtime.

Despite the danger present, Hull goes into town anyway. His rationale is with so many of their supplies now ruined, he doesn’t really have a choice. He needs to replace the necessities lost so that he, Sarah, and Meghan can continue surviving until they strike enough gold to begin making a proper living. Unfortunately for Hull, this ends up being another indicator of the direness of his situation. While gathering what he needs from the general store, the owner cuts him off, revealing that he has an extensive tab running back over six months and totaling more than $86. Remember, this film’s set during the Gold Rush era, a time where $86 was roughly equivalent to $3,500 today, and that’s not taking into account how much more expensive goods tended to be in Gold Rush California. Hull manages to convince him to let him take this last bundle of supplies, but it’s the last chance he gets. If he can’t pay the next time, he gets nothing.

The situation only worsens as Hull begins loading his wagon. Four of LaHood’s miners have spotted him, though calling them miners is generous since these men act as bruisers more than anything. Cornering Hull as he tries to leave, and doing so only after each grabbing an axe handle from a bucket outside the general store, the four men interrogate Hull as to why he’s in town before proceeding to beat him and threatening to burn his goods. It’s at that moment, as the boss of this group strikes up a match, that he’s doused with a bucket of water from offscreen and we finally meet our stranger.

At this point, an unusual fight scene ensues between the nameless rider and LaHood’s goons. Armed with an axe handle of his own, he takes on the four men with shocking expertise, blocking and parrying their swings with the hickory axe handles - we know this because of a later line he speaks: “There’s nothing like a nice piece of hickory.” He swiftly disarms them, fighting them back as he not just brandishes, but flourishes that simple axe handle. Even when they go for their guns these goons stand no chance, ending up even more beaten and bruised than they left Hull.

This scene stuck out to me on my first watch because it’s a highly unusual choice for a western. The stranger treats the axe handle almost like its a sword; parrying and deflecting, twisting the axe handles of the goons out of their hands, even spinning it in a showy flourish at one point. It’s a scene that feels like it would be more at home in a Chinese martial arts movie or some pulpy 80’s fantasy along the lines of Conan, not in a relatively down-to-earth Western. However, it’s handled in such a matter-of-fact way that even with it being over the top, it doesn’t quite feel out of place. It does raise questions about the stranger, though, and that’s really the point of this scene. A point that’s highlighted when Hull invites him to his home to repay his good deed with “three hots and a cot.”

The stranger’s presence fast becomes a point of contention between Hull and Sarah. After hearing what happened, Sarah’s grateful for the fact the man essentially saved Hull’s life, but she’s frightened by the account of how efficiently he dispatched the goons. She’s convinced he must be some kind of outlaw, a gunfighter perhaps. Certainly a killer, because why else would he be so ruthless? Hull understands her objections, but doesn’t take them to heart. Far as he’s concerned, the man can’t be all that bad because he went out of his way to save his life when he had nothing to gain for it.

As the argument draws on, we see the stranger changing his clothes in the other room. When he emerges and addresses them, politely stating that he hopes he’s not the cause of their argument, Hull and the two Wheeler women can only stare in shock at what they see: a white collar around his neck. The stranger is a preacher, and this is how he’s referred to throughout the rest of the movie.

From this moment, the events of the movie escalate in their intensity. Coy LaHood’s son, Josh, is made aware of what happened to his men in town when they show up late to their shifts at the LaHood mine. This is our first introduction to the way LaHood does things. Where the prospectors are living humble lives working with and around the nature surrounding them, LaHood has set up a massive strip mining operation using powerful high-pressure water cannons to wash out massive sections of the surrounding mountains into their sluice to extract the gold in bulk quantities. It’s a highly destructive method of mining, one which genuinely has seen entire mountains removed from existence across our history1.

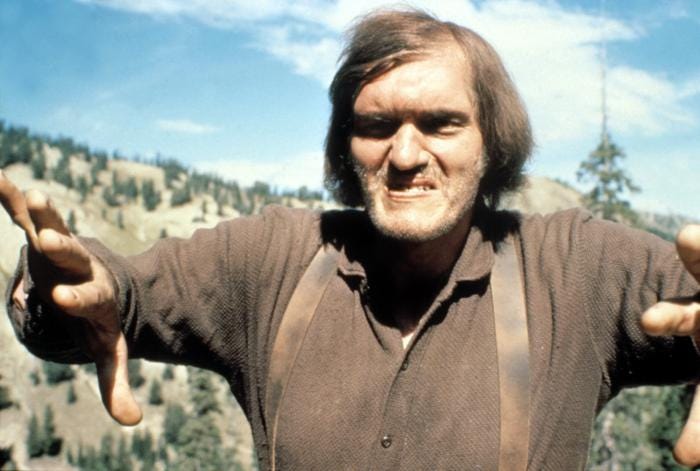

Hoping to put an end to this new problem before it can worsen, Josh heads into the prospecting community with the biggest man on his crew at his back. This giant is known simply as Club, and is played by Richard Kiel, who made a name for himself in the James Bond franchise as its only recurring goon, Jaws. Like Jaws, Club is a goon and a bruiser, though you won’t find him biting through any high tension steel cables in Pale Rider. As a brief aside, Club actually gets something of a small character arc in this movie, which was a pleasant surprise to me on my first viewing. It goes to show that for as scary as this giant of a man appears to be, he’s not so unscrupulous as many of his fellows.

In any case, Josh and Club head into the prospectors’ camp to deal with the Preacher, discovering his true profession in the process. Preacher ultimately drives them off by subduing Club, notably only using as much force as is necessary to do just that. Once rendered unable to fight by a knock to the head and the family jewels by the sledge Preacher was using to help Hull with some of his daily work, Preacher then proceeds to gently guide Club back to his horse and politely recommends Josh bring him back to the LaHood mine and get him some ice for the swelling.

This sort of action on Preacher’s part is notable throughout the movie. In defiance of the expectations we may have from Eastwood’s prior Western outings, Preacher never seeks to act with violence. He only responds with it, and only when a threat has been placed against him or this new flock he’s found. Even when he eventually comes face to face with LaHood later in the movie, he makes no attempt to fight the man or force him into compliance with violence. He simply talks, relying on his goodly principles in an attempt to petition LaHood’s better nature in an effort to find a peaceable solution. That said, Preacher will only offer a solution. It’s ultimately up to the prospectors to decide if they’ll accept it or not, as it’s their livelihoods that LaHood has put in his crosshairs.

Unfortunately, greed is a powerful vice, and it’s what drives LaHood to take the actions he ultimately does. After arriving in Carbon Valley by train and meeting his son and one of the men who was beaten by Preacher after assaulting Hull, LaHood’s informed of what happened. He’s absolutely incensed when he hears that a preacher has arrived in the prospectors’ camp, recognizing that the faith he could give them would be more than enough to restore their resolve. So it is that when Preacher joins Hull and the Wheeler women the next time they go to town, LaHood first tries to bribe him with the promise of setting him up with a thoroughly comfortable life as the preacher of LaHood town. The Preacher denies him, stating, “You can’t serve God and Mammon both, Mammon being money.”

At this, LaHood attempts to trick him into accepting the bribe by producing false documents claiming that he, in fact, has the legal rights to the claim in Carbon Canyon, which Preacher already knows to be false per a prior conversation with Hull. Again he denies LaHood, so LaHood promises to bring violence by turning to a dangerous man: U.S. Marshal Stockburn, and his six deputies. A man which Preacher his hinted at having some history with, as he recognizes the name. At this point, he asks LaHood if he’d be willing to buy out the prospectors’ claim, pushing to see if he’d be willing to go so far as spending as much as $1000 per head. Mind you, that’s about $40,000 per person in today’s money, not a small amount. Reluctantly, LaHood agrees, but only once Preacher presses him with the question of how much a clean conscience is worth to him.

The prospectors debate the situation that night. Some are willing to sell, thinking LaHood’s offer is a fair deal. Others, in particular Hull and Spider Conway, are against the idea, recognizing that LaHood would only make that offer if he stood to gain considerably more than he’d lose by paying them off. Hull’s approach is more honorable. Petitioning to the good, hard working nature of the men present, he asks them why it is they really stuck around. If money’s the only reason, they ought to take LaHood’s offer, but for him, it was to make a better life for himself and the Wheeler women, whom he’s come to love. He stands as an example of the American spirit, a man seeking his dream of family and freedom.

In the end, they refuse LaHood’s deal. Carbon Canyon isn’t just a mining claim to them anymore, it’s their home, and they won’t be driven out. Problem is, as Sarah soon brings up to Hull, the men made this choice with the expectation that the Preacher would be around to help protect them. Thing is, he disappeared the next morning, and no one’s quite sure where he’s gone. No one except for us, the viewer, that is. Knowing that their refusal means Stockburn and his men will soon be arriving, Preacher rides off to a city that’s presumably nearby, where he enters a Wells Fargo bank to have a lockbox brought out for him.

A lockbox containing three revolvers, two full-sized and a smaller one for hiding on one’s person, and bullets to go with them.

From here, the situation ramps up to the final conflict between the prospectors, LaHood and his mining company, and Marshal Stockburn. And as the violence begot by LaHood’s men escalates, so to do the reprisals enacted by Preacher and, eventually, by Hull as well. Like for like, an eye for an eye. It’s but one of the many concepts of faith explored in the movie, paralleled beside the conflicts of means and aims that were formed as people settled in the Western Territories.

This is a massive part of why I find Pale Rider to be so thoroughly compelling. There is a genuinely massive amount of layered storytelling going on in what is, on its surface, a very straightforward tale. Concepts of faith are showcased between the Preacher, LaHood, Stockburn, and Hull; and these are then played against by the various legal and ethical questions being posed in the movie’s narrative. All together, it presents us with a nuanced view of the various ways people attempted to live their lives in the Old West, but where Unforgiven is more unabashed in cracking open the romanticism the era is presented in, Pale Rider makes use of it to help portray the higher ideals of the American spirit.

Parallels are frequently used to showcase these higher ideals, points of conflict set up between the differing points of view of core characters. Hull and Coy LaHood are one such example, each of them showing the different sides of life found in the profession they chose as miners. LaHood made his fortune with mining, enough that he was able to force out the other prospectors in his area, establish an entire town, and build a massive operation that funds said town. However, his method for doing so required forcing others out of business and blasting the land barren, which we see in every scene that takes place in his mine.

By contrast, Hull and his fellow prospectors are people of lesser means living simpler lives, but those lives are shown to be more fulfilled by family, loved ones, and what can be earned by the sweat of one’s brow. They struggle to make ends meet, especially under the pressure LaHood’s men put on them. However, their faith is rewarded when the Preacher arrives in answer to Meghan’s desperate prayer. These are men and women who just want to make their own way in life, but as is so often the case, folks like LaHood can’t abide that for long. People like these prospectors will always end up in the path of the long-reaching avarice of men like LaHood.

LaHood’s son, Josh, provides a similar parallel to Meghan. Meghan is a lot like Hull, she wants to be free to live a good life. She wants to fall in love with a good man and start a family, and in her youthful ignorance she thinks she sees that opportunity in Preacher. Hinted at as being far more world weary, though, he gently rebuffs her advances, which she angrily balks at, causing her to lash out. This is a product of her youth, she doesn’t yet understand the true value of what she wishes to give away, though she thinks she does.

Josh similarly learned values from the father figure in his life, which is his actual father in this case. For whatever vileness he shows, I can at least grant Coy LaHood the credit of not running out on his child the way Meghan’s birth father did. Still, that doesn’t do the man much credit, as Josh gives us a more extreme presentation of how far LaHood’s purely profit driven ideals can push a man. He’s brash and selfish, and when the opportunity presents itself for him to try and force himself on Meghan, he takes it, and disgustingly he does so to the cheers of the miners in his employ. The one exception to this is Club. Despite the film hinting at him being “simple,” as they’d term it at the time, Club recognizes the wrong in what’s being done to Meghan and moves to stop it, and he likely would have if not for Preacher miraculously arriving in time to prevent it first. Happily, the story still does give Club a chance to showcase his truer, goodlier nature later in the film.

Alongside Hull and LaHood, though, the other major contrast in the film comes in Preacher and Marshal Stockburn. Similar to LaHood, Stockburn is a man who twists the letter of the law to his own ends, as showcased in his introduction to the film where he and his deputies harangue a drunken Spider Conway. After breaking it big and finding a chunk of rock laced with a couple pounds of gold, Spider brings his sons into town to celebrate and gloat. Unfortunately, he does so on the day Stockburn arrived, and as he drunkenly shouts insults at LaHood outside his office, the Marshal and his deputies line up to confront him.

They proceed to humiliate and terrify Conway, firing at his feet to make him “dance” for their amusement. Stockburn’s demeanor tells all. He knows precisely what he’s doing, and when he finishes by shooting the bottle and the ore laced stone out of Conway’s hands, he knows that’s going to frighten the drunken prospector into attempting to draw, thus opening the legal avenue needed for he and his deputies to gun him down as an example to the others. It’s a harrowing and brutal scene, easily the most violent in a movie that’s been quite tame in that respect until now. Worse yet, the Marshal and his men gunned Spider down in front of his two sons, forcing the kind young men to watch their father die a painful, bloody death.

It’s a declaration of war, and it sets Stockburn on a collision course with Preacher, who each have history with one another. We’re never outright told what this history is, but we can infer it based on hints left in the film, chief among them being the series of six bullet scars we see in Preacher’s back while he’s changing clothes on that first night he spends with Hull and the Wheeler women. It’s also the clearest showcase of how different these men, or rather these conceptual forces occupying the bodies of men, are. Where Preacher has exercised restraint and acted as a generally positive force throughout the film Stockburn’s reaction to the taunting of Conway, something which Preacher would’ve countered with smartly worded rebuttals, is to react with violence from the outset and goad the prospector into a situation where he’d be legally permitted to kill him.

All of this done for no other reason than to make an example, and that example only needed to be made because he was being paid to make it. Like LaHood, Stockburn is willing to put a monetary cost on the lives of other men, indirectly calling back to what Preacher told LaHood earlier in the film: “You can’t serve God and Mammon both, Mammon being money.”

The contrasting parallels between Preacher and Stockburn are present even in the sound design of the film. Something interesting that I noticed about Preacher when I revisited the movie this last weekend was that every time he was walking on screen, you could hear his steps. The spurs he wears jingled like small bells, announcing his presence in a musical manner. After watching it, I took this as an audio metaphor for what he’s meant to be in the film: an avenging force. The Pale Rider, sat atop his pale horse, come to mete out just and appropriate retribution. As he rides, as he walks, you hear the ring of his spurs. The ring of small bells. The toll of bells.

It’s no coincidence that when she first sees him, Meghan is reading the passage in the bible dealing with the Four Horseman, and he rides into view as she’s reading of Death.

What I didn’t catch on this last watch was something I only just confirmed while writing this essay. In the image of Stockburn and his deputies above, I noticed that they, too, appear to be wearing spurs. This made me curious, were theirs audible as they walked, too?

Bringing up the scene where they confront Spider Conway, I confirmed that yes, they are. However, the sound is dull and flat, devoid of the chiming musicality of Preacher’s spurs. Stockburn and his men are death dealers, and as such, their spurs also ring like the tolling bell. However, there’s no music in it, no beauty, for theirs is not just action. These men may be men of the law on paper, but in action, they’re naught more than murderers. Compared to the musical lilt of Preacher’s spurs, the dull clinks of the Marshals’ further reveals their leader’s position as the dark reflection of the mysterious Preacher.

I could go on and on about this movie, I really could. It’s not as complex as Unforgiven is; the story it presents is far simpler on the surface, but that allows the various elements woven into it to shine well. However, that also means it also lacks the same level of expertise present in its predecessor. And I do mean predecessor, because I think in many ways Pale Rider is something of a first for Clint Eastwood at the kind of movie Unforgiven would end up being.

Even so, I wouldn’t consider Pale Rider to be a lesser movie in any sense. It’s a beautifully crafted film, one rich with meaning that, quite appropriately, waits to be mined out of it. Some of its ideas are easy to grasp, presented right near the surface as they are. Others require a bit of deeper digging, though, and that’s fine. Actually, it’s more than fine, it’s downright fantastic. Pale Rider is the sort of movie that’s easily rewatchable, because there’s always something more to be gleaned from it. And once you reach the point where you’ve gleaned all that can be gleaned, it’s still easy to rewatch because it’s just a damn good Western in its own right.

My first novella, In the Giant’s Shadow, is available for purchase! Lured to the sleepy farming community of Jötungatt by a mysterious white raven, Gaiur the Valdunite soon finds herself caught in a strange conspiracy of ritual murder and very real nightmares.

Purchase it in hardback, paperback, or digital on Amazon now:

Last year, I learned that this fate nearly befell some of the mountains in the Cuyamaca State Park in California, about 45 minutes away from where I live. That area, in particular around the town of Julian, marks a famous piece of Southern California’s history with the Gold Rush. Some of the mines around the region are still accessible, though I wouldn’t recommend randomly exploring them since there are many unstable areas inside them. However, one such mine is still accessible in the town itself, with historical tours run through two levels of the mine. While these are tailored to be understandable by school children, the history of the town’s mining operations is fascinating nonetheless, and made all the moreso by the fact that some locals still engage in forms of prospecting to this day, taking advantage of a lot of the finer gold dust left in the dirt that was overlooked by the miners of the time.

Fortunately for all of us who enjoy visiting the town and the surrounding state park, ordnances were passed which ultimately outlawed strip mining operations like LaHood’s.

Excellent! I may watch the movie again, together with my brother. He is a massive Clint Eastwood and western fan.

Excellent essay. It is hard for me to pin down my favorite Eastwood western, but this has always been in the top 3. What do you think about the people who saw this as a type of continuation of “High Plains Drifter?”