Bran Mak Morn and the Picts - Robert E. Howard's Enduring Fascination

For Robert E. Howard Days, 2025

Before we begin, if you’ve been enjoying my work and would like to further support my fiction, essays, and book reviews, the following are the best ways to do so:

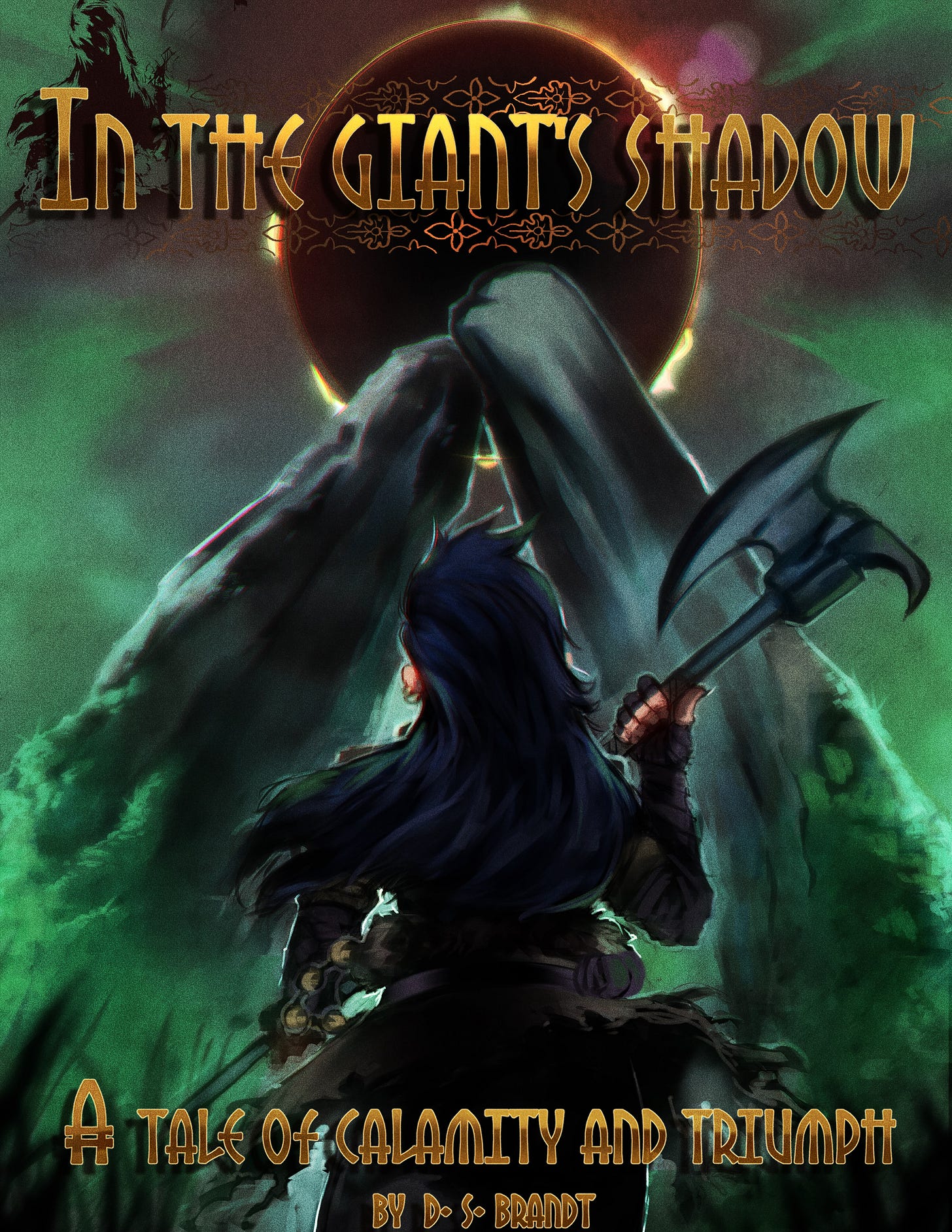

Purchase my book, In the Giant’s Shadow. You can find it on Amazon in hardcover ($19.49), paperback ($11.99), and digital ($3.99) formats. This is the method I most recommend as it gets you something tangible in return for your financial support.

You can subscribe to Tales of Calamity and Triumph for either $5 per month or $50 per year. Doing so automatically unlocks digital versions of any and all of my current and future published fiction.

Restacking and sharing work of mine which resonates with you is the easiest (and arguably most effective) way to help.

As always, please don’t feel pressured to do any of these things. Your readership is more than enough for me. Thank you kindly for giving my words your time.

When you read the name Conan the Cimmerian, (or Barbarian,) it’s a safe bet the vast majority of you will have an idea of the character in question. Perhaps you see in your mind an image of Arnold Schwarzenegger wielding his two-handed sword, thinking on the Riddle of Steel and speaking on what is best in life–“To crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and hear the lamentations of their women.” This would hardly be surprising, as the films Conan the Barbarian and Conan the Destroyer are two of the most well known adaptations of the character. Yet this is Substack, and you’ve come here to my publication to read my thoughts on Robert E. Howard, which means it’s very likely you know him best from his written works.

Indeed, that Conan is the most well known of Howard’s stable of characters is beyond argument. Yet there were many others he wrote before he came to Conan, many of which also endure to this day. Chief among these lesser known characters is likely the one who stands as my personal favorite, the puritanical hunter of monsters and wicked men, Solomon Kane. While not as popular and widely recognized as Conan, Kane still casts his own shadow across the creative world. A number of tropes we’ve seen popularized in dark fantasy media can be drawn back to Solomon Kane, with perhaps the most notable of them being the archetype we imagine when we think of witch hunters or inquisitors in fantasy stories.

Fair though it is to say that Conan and Kane are the farthest reaching of Howard’s characters, they’re far from the only one’s he’s written, and far from the only ones of influence. His very first published story, a 1925 tale of warring cavemen titled “Spear and Fang,” has a direct line of influence with Genndy Tartakovsky’s primitive sword & sorcery animation “Primal,” as indicated by the fact that Genndy named his two main characters, the caveman Spear and his T-Rex companion Fang, after the title of that story. Then you’ve got the adventure stories of the sailor Steve Costigan, who was a stand-in for Howard himself and whose stories were partly autobiographical. And then there are the stories of the barbarian king Kull of Atlantis, who would rise to become ruler of the ancient kingdom Valusia.

Kull is another of Howard’s older characters that has a rather storied history to him. Many of you are doubtless aware that Kull is widely considered to be a precursor to Conan. Like the renown Cimmerian, Kull was a barbarian who would become an adventurer and king. He would prove himself not only through his strength and valor in battle, but by his honorable manner as well. Kull would come to conquer the fallen kingdom of Valusia by freeing it from the yoke of the vile snakemen, a theme we later see repeated in the 1982 film Conan the Barbarian with James Earl Jones’ villainous character, Thulsa Doom, a ancient hypnotist sorcerer who is able to transform into a massive python. Fun fact, Thulsa Doom was never actually a villain of Conan’s until that movie, and was originally written by Howard as an adversary for Kull.

Howard ended up writing a handful of stories featuring Kull, though a number of them were never completed before he moved on to write about different characters. This was apparently a common theme for Howard, as confirmed by some of the letters he wrote to his good friend, now-famed horror writer, H. P. Lovecraft. To paraphrase Howard’s words, he states in his letters that his characters come to him fully formed in his mind, and when those characters come, he writes for them until his time with them is done. When that happens and why doesn’t seem to have any particular rhyme or reason, but looking over the timeline of his stories, we can get an idea of how this played out, thanks to the fact that we can see very specific spans of time for which he wrote for these characters.

Conan was the last of Howard’s characters before he ended up taking his own life on June 11th, 1936. He was 30 years old, and at the time of this writing, yesterday marks the 89th anniversary of his unfortunate suicide. Before Conan, he wrote Kull. Before Kull, he wrote Solomon Kane, and before Kane was Steve Costigan, as well as a scattering of a few other stories here and there. As I said, when you dig into the timeline of Howard’s works, you can see the habit he wrote to Lovecraft about on full display.

However, as is so often the case in life, there is an exception which proves Howard’s rule. That exception exists not in a singular character, but rather in a race of people who are featured across a broad swathe of his stories. That race is called the Picts, and it’s a race of men that historians in Howard’s day believed to be real. In that same letter to Lovecraft, Howard details his fascination with this race, which he first read about in an Irish anthropological text when he was thirteen. In his letter, Howard describes himself as being not just fascinated by the idea of this ancient race, but sympathetic towards them, despite the fact that the author of the book he was reading did anything but portray them in a positive light.

Described as short men of a dark complexion, the Picts that Howard read about were believed to be mongoloid in nature, likely originating from somewhere deep in Asia, and were portrayed as foragers or farmers with no battle acumen to speak of. Howard’s earliest depictions of the Picts reflects this in part, though he did away with the idea of them being simple foragers and imparted to them a history of conquest and empire building that we can see reflected in his later works. One of the finest examples of this comes from the Kull stories. In those tales, Atlanteans like Kull view the Picts as their bitter enemies. However, as an example of greater wisdom and honor than his fellow barbarians, Kull ends up befriending one of the mightiest pictish chieftains of his day; Brule the Spear Slayer.

This is hardly the only pictish character to appear in Howard’s stories. In fact, the Picts remain a powerful force even in Conan’s Hyborean Age, which takes place many thousands of years after the time of Kull and Atlantis. Yet there are few, if any, named Picts that appear in the Conan stories, at least insofar as I can recall. It’s possible that some of my contemporaries such as

, , , , or may remember better than I.The Picts weren’t only relegated to the stories of other characters, though. Howard wrote tales of the Picts numerous times across his writing career, including a number of historical fiction stories set in the days of the Roman Empire’s expansion across Europe. In these stories, Howard’s depiction of the Picts changes from his earliest iterations, which were distinctly more monstrous in nature. This newer take on the ancient race portrays the remnants of a once proud people, inheritors of empires long lost who would rise up, build their grand nations, only to eventually fall and be driven into new lands. A once strong and noble race made savage and primitive as they were forced to interbreed with other peoples to survive, losing their culture in the process. A people who believed that one day, a king would arise among them, noble and pure like their ancestors were.

That character, that man, is Bran Mak Morn.

Bran Mak Morn is a very unique figure in Howard’s literary life, and not just for the fact that his stories take place in the historically recognizable time of the Roman Empire. This aspect on its own isn’t particularly standout. Solomon Kane’s stories also take place in a recognizably modern era compared to the works of characters like Kull and Conan, or stories like “Spear and Fang,” with Kane’s stories taking place in the 1600’s. However, the stories of Bran Mak Morn and the Picts are decidedly different in their feel compared to the likes of the comparatively more modern adventures of Kane and Steve Costigan. These are brooding tales of an ancient and fading people trying in vain to reclaim their place in the world, and they frequently lean on the concepts of ancestral memories, old gods, and at times, cosmic horror.

Yes, you read that right. One of the things that makes Bran Mak Morn unique among the rest of Howard’s characters is the fact that it’s through him that we get the most direct contributions to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos that Howard ever wrote. We’ll touch back on this later, though. There are other aspects of Bran Mak Morn and Howard’s enduring fascination with the Picts that we needs cover first before looking at what is rightly considered one of his finest stories.

There has long been a touch of mythology and mysticism in most of Howard’s stories. Often times these powers end up following his characters, particularly in the case of Solomon Kane. Naturally, Kull and Conan also aren’t strangers to the magical and mystical. Many of their adventures see them pitted against otherworldly creatures, wily hypnotists, or evil sorcerers. Two of the most revered Conan short stories, “Tower of the Elephant” and “Queen of the Black Coast,” are beloved in part because these adventures pit him against dangerous and unsettling monsters. In the case of the former, we can see more of Lovecraft’s influence on his friend, while the latter is in some ways a throwback to the Solomon Kane story, “Wings in the Night.”

Many stories of the Picts, and most that directly feature or mention Bran Mak Morn, carry similar touches of myth making and the supernatural, touches which I would argue are more potent given the more modern settings. Note that this isn’t to say that the stories of Bran took place in what was Howard’s modern day. Rather, they take place in a historically recognized time, and often without the dark and eerie flourishes present in Solomon Kane’s adventures across Elizabethan England, Europe, or the wilds of “darkest Africa,” as Howard puts it in one of his earliest Kane stories.

Instead, the stories of Bran and the Picts straddle a line between the heroic fantasy/sword & sorcery genre that would emerge from Howard’s works, and historical fiction. We can see this reflected in the letters and essays where he writes of his intentions with his stories. The world he creates is not some new world, but rather earlier eras of human civilization on Earth as he imagines them. Kull is of Atlantis, a mythical city from Greek legend that all of us surely at least have passing knowledge of. Kane roams Europe and Africa in pursuit of wickedness to root out, his stories set in an age that is very well documented historically. Steve Costigan, as a stand-in for Howard himself, is the most relatively modern of his characters. Bran Mak Morn, last of the pictish kings, lives in the days of Rome’s expansion and is expressly stated to be of Mediterranean stock. The one era that is the most removed from an immediately recognizable historic or mythological concept is Conan’s Hyborean Age, which Howard spent many years developing across the course of his writing career, and still draws lines back to Kull’s Atlantis.

In this way, Bran Mak Morn and the Picts fit very nicely into Howard’s fictionalized concept of history. They’re a people who have had a presence since the earliest stage of his connected eras, Kull’s Atlantis, and remained influential all the way to Howard’s modern day. In fact, there are at least two stories which revolve around the Picts that, in whole or in part, take place in, or at least very close to, Howard’s time. One such story, “Children of the Night,” involves an educated group of friends meeting to discuss numerous ideas of philosophy, history, and anthropology that were being popularized at that time. Ancestral or genetic memory was one of these concepts, and acted as a central conceit for this story’s action packed middle section.

As a fun note, after reading this particular story, I was able to once again see Howard’s direct influence on Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal, specifically on the season 2 episode, “The Primal Theory.” That episode runs on a very similar premise to the story above, featuring a group of English scientists engaging in gentlemanly debate over the nature of modern man versus his primitive ancestors. Their debate touches on many similar ideas to those Howard draws upon for “Children of the Night,” though it is quite different in that the idea of ancestral memory isn’t present.

Instead, their suggestions of modern man’s difference from his more violent primitive ancestors is tested when a violent lunatic who escaped a local asylum breaks into the manor house where they hold the debate, forcing the men into a fight or die situation. Amusingly, much like this episode of Primal calls back to this story of Howard’s, Howard also makes direct references to the work of some of his friends and contemporaries in this story. There are also subtle references in this episode that call back to the far more linear story of Spear and Fang that we follow for the rest of the season.

The point is the Picts have a presence across a huge swathe of Howard’s work, indicating his unique fascination with these people. As such, you might expect that he wrote a good many Bran Mak Morn stories that were interspersed with the rest of his work. It would stand to reason, given his fascination, yes?

Well, no. Only a handful of stories featuring Bran Mak Morn exist. Of that handful, only two are actually told from Bran’s perspective: “Kings of the Night,” and the highly lauded, “Worms of the Earth.” I’ll touch on both of these soon, as I do believe they’re the two best stories featuring the pictish king.

Most of the stories that involve Bran don’t involve him as the focal character. Instead, he’s panted as something of a legendary figure, a mighty king who’s singularly capable of uniting the savage and devolved people the Picts have become in the time of the Roman Empire. His enemies speak of him with fear and reverence, and Howard commonly portrays their surprise when they finally get a chance to see him, at least on the occasions that they do.

Yet for as often as Bran Mak Morn is mentioned in the collected stories that are supposedly about him, he just as frequently doesn’t appear in them as he does. In fact, in total there were only five works published which are considered Bran Mak Morn stories. Beyond that, a small handful of excerpts and incomplete manuscripts, and at least one poem, either briefly show or make mention of the pictish king. This has led to a little frustration among some Howard fans surrounding the collection Bran Mak Morn: The Last King. You would think that, given the title, Bran would be the book’s chief focus. However, there are many times where the writers who put the collection together are clearly more interested in Howard’s fascination with the Picts than how he represents that fascination through Bran Mak Morn. Personally, I didn’t mind this overmuch, as it did give some compelling insights into Howard’s life and mindset at the time, thanks to his included letters.

What I did mind about this collection was twofold. The first issue is Howard’s own, and that’s his tendency to drag in some of these stories. This is most common to the stories that don’t actually feature Bran Mak Morn, or feature him very little. I personally find the most egregious example of this is the first pictish story Howard had published, “The Lost Race.” When he first submitted this story to Weird Tales, Howard’s editor sent it back to him with numerous notes relating to a major central criticism: it reads more like a dissertation on the pictish race than an actual story.

Obviously, considering the fact the story was published, Howard made some of the suggested edits and resubmitted the story, at which point it was accepted. However, the issues noted within it still remained present. Doubtless reduced compared to his original manuscript, but present all the same. The result was a reading experience which I found interesting in the same manner that I find historical documentaries interesting. Howard’s fictionalized account of the pictish people is fascinating as a piece of worldbuilding and makes for an interesting glimpse at his original idea for his version of the race. Taken as a story, though, I find it to be on his weaker side; useful in how it allows us to see the way his concept would evolve the more he wrote of the Picts and their last king, but not particularly interesting as a story in its own right.

The second issue with the collection is, quite frankly, the fact that a large chunk of the stories and manuscripts included in it have nothing at all to do with Bran Mak Morn. Now in fairness, most of these are listed in the miscellanea section of the book, but not all. “The Lost Race” is included as part of Bran Mak Morn’s section, a decision I might understand if it were included at the start of the section to help highlight where Howard’s stories of Bran and the Picts began. Instead, it’s the second-to-last entry, sandwiched between “The Dark Man,” a story which takes place centuries after Bran’s death and places him in a mythological role, and the short poem “Song of the Race.”

Personally, I find this decision more than a little baffling. While a good chunk of the miscellanea entries are related to Bran Mak Morn, most of these are little more than fascinations, such as the pre-edit draft version of “Worms of the Earth” or the untitled and unfinished stage play and novel manuscripts that were both planned to feature Bran Mak Morn, but were never written to the point he was actually included in them. If you’re a big fan of Howard and eager to get into some of the history, these are quite enjoyable for that. However, if you’re here specifically for stories involving Bran Mak Morn, you may find there’s a good deal less of him in this book than you might expect, particularly given the collection’s title. I can’t help but feel it would’ve been more appropriate if they titled the book something along the lines of, Bran Mak Morn and the Pictish Race.

All that being said, there are absolutely gems to be found hidden within these stories. As mentioned earlier, there were two stories in this collection that were standouts to me. The first is “Kings of the Night,” which sees the pictish king leading an army of disparate tribes and peoples against an encroaching Roman force. Unfortunately, Bran’s situation is dire. Some of the gathered armies on his side, including two powerful forces of Celts and Northmen, are on the cusp of defecting to the Romans. The reason is due to the death of the Norse king who once led the Northmen. That king promised to fight for Bran in payment for an old debt, but the man who now leads them refuses to see that promise through unless Bran can do the impossible and find a new king to lead them.

This situation builds to one of the first instances of mysticism we see in a Bran Mak Morn story. On consulting with his shamanic advisor Gonar, Bran reluctantly takes his advice to wait and trust that a king will show himself. He’s not fond of this idea. In fact, he’s extremely worried that the attempts of these gathered forces to drive the Romans back will amount to nothing, because how can he possibly hope to find a Norse king to lead the Northmen in a single night?

The answer comes through Gonar’s mysticism, and they reveal that he may actually be as ancient as the whispered rumors about him say. The reveal of who Gonar brings to lead the Northmen is a large part of the fun, and I’m hesitant to mention the name here so that those who haven’t yet read “Kings of the Night” can enjoy it unspoiled. The other major source of enjoyment is in Bran’s juggling of the tenuous relationships between these varied groups, which is primarily shown through his interactions with the leader of the Celts and the new leader of the Northmen. The difficulty Bran faces is in the fact that these gathered people have long been enemies and rivals to one another. They’ve contested each others lands, waged bloody war, and fostered lengthy grievances that were present before many of these men were born. It’s only the threat of Rome that binds them together, but with the large force of Northmen threatening to defect, Bran’s defense against the Empire is poised to collapse before it can begin.

“Kings of the Night” wraps up its compelling narrative with the battle against the gathered Roman forces. Honestly, this is one of the weaker parts of the story, though that’s not to say it’s bad, because it isn’t. The battle has its moments of excitement and the conflict feels appropriately bloody and brutal, as we would expect from Howard. The issue is more in the pacing and the scope. I felt the battle wrapped up a little too quickly, which contributes to the difficulty Howard seemed to have in capturing its scope. Even with this problem in mind, though, the battle remains exciting, and the story we get is largely quite satisfying.

Yet where “Kings of the Night” is a somewhat flawed but entertaining bit of historical fiction with a splash of mysticism thrown in, “Worms of the Earth” is one of those stories that shows us Robert E. Howard at his very best. Unlike most of Bran Mak Morn’s stories, and that includes “Kings of the Night,” “Worms of the Earth” is wholly for Bran Mak Morn. In fact, I would say it’s the character’s defining story.

Opening on the scene of a Pict being executed by crucifixion on the orders of the Roman governor Titus Sulla, “Worms of the Earth” builds from this moment into a darkly emotional tale of guilt, hatred, vengeance, and dark secrets better left buried. The Pict being executed appears at first to be a man of little consequence. Bound to a rudely constructed cross, he’s described as being, "half-naked, wild of aspect with his corded limbs, glaring eyes and shock of tangled hair." He never speaks and is never named, adding to that inconsequential feeling. However, as he struggles against the Roman soldiers as they prepare to nail him to the crucifix, he keeps staring at one man amongst the crowd.

This man is a fellow Pict named Partha Mac Othna, an emissary sent by Bran Mak Morn to treat with Sulla and his forces. Partha Mac Othna objects to the execution, arguing that it feels wrong that this should be called justice when he sees, "that the subject of a foreign king is dealt with as though he were a Roman slave."

Sulla entertains his argument, albeit only briefly. He counters that the prisoner was tried and sentenced in an unbiased court, but Partha Mac Othna is unconvinced, leading to the following exchange:

"Aye! And the accuser was a Roman, the witnesses Roman, the judge Roman! He committed murder? In a moment of fury he struck down a Roman merchant who cheated, tricked and robbed him, and to injury added insult—aye, and a blow! Is his king but a dog, that Rome crucifies his subjects at will, condemned by Roman courts? Is his king too weak or foolish to do justice, were he informed and formal charges brought against the offender?"

"Well," said Sulla cynically, "you may inform Bran Mak Morn yourself. Rome, my friend, makes no account of her actions to barbarian kings. When savages come among us, let them act with discretion or suffer the consequences."

This exchange, as well as the remainder of the execution scene, makes clear that while this man is of no particular consequence to most, Partha Mac Othna feels something deeply for him. He sees what’s being done as an inherent wrong, a vile transgression. Rather than allowing Bran Mak Morn, the king of the accused, to render judgement, it is Rome, and by extension Sulla, who take it upon themselves. However, equally important is the recognition in the eyes of the accused Pict. Throughout the scene, he keeps looking to Partha Mac Othna, silently begging him for aid. He recognizes the emissary, clearly believes him capable of saving him from the long, torturous death the Romans have in store for him.

Ultimately, Partha Mac Othna can do nothing, though he desperately wants to. It’s only through daring chance that the prisoner gets his mercy, when he spits out the wine the Romans offer him after mounting him on the cross. He happens to do so in the face of a young Roman officer named Valerius who, in a sudden fit of youthful anger, stabs the Pict in the chest with his sword, denying a now angry Sulla the lengthy punishment that would’ve made the unnamed man an example for the others like him living in or around Roman territory.

The execution scene is one of the strongest openings to any of Howard’s stories, and the quality of “Worms of the Earth,” a five chapter novelette just shy of 12,000 words, is either maintained or improved from there. That said, what really helps to sell the power of this scene is the one that comes next, where it’s revealed that the emissary sent to treat with Sulla in the name of the pictish king is, in fact, Bran Mak Morn himself. This is the reason why the Pict on the cross recognized him. Where Sulla, the surrounding Romans, and Sulla’s contingent of Rhineland bodyguards saw nothing more than an emissary who happened to be more stately and eloquent than the rest of his savage ilk, the Pict on the cross was looking into the face of his king, and his king watched him die.

Bran does not take this well. Beyond incensed, he’s insulted, infuriated, and grieves deeply for this unknown subject of his. He still sees the man’s eyes boring into him. Grom, a Pict who accompanied Bran as an aide and is not unlike the executed man in his appearance, attempts to convince Bran to maintain his calm, to not act rashly or in overt harshness, but Bran won’t heed him. He’s haunted by the face of that man who’s name he never knew, who nonetheless looked to him with desperate, silent pleas of rescue. Another member of his dying race, executed right before his eyes by the machine that is Rome.

Recall earlier that I mentioned how Howard developed a direct tie into the Cthulhu Mythos with Bran Mak Morn? “Worms of the Earth” is the story wherein this occurs. Unwilling to let this slight stand, unwilling forgive what was done to one of his own people by Rome, or to forget the disrespect Sulla showed him, Bran invokes the Nameless Gods and Cthulhu’s ancient home of R’lyeh. He swears that, "men shall die howling for that deed, and Rome shall cry out as a woman in the dark who treads upon an adder!"

And that is precisely what Bran seeks to achieve. He can’t bring himself to forgive what was done, not because the executed Pict was of any particular import, but because of what he represented. To the mind of Bran Mak Morn, the execution of one of his own by Roman rule of law, is a failing on his own part. He is the Last King of the Picts. It is his duty to protect his people, to lead them back to a position of greatness and civilization under their own rule. As Bran himself says:

"My people look to me; if I fail them—if I fail even one—even the lowest of my people, who will aid them? To whom shall they turn? By the gods, I'll answer the gibes of these Roman dogs with black shaft and trenchant steel!"

I shan’t dig deeper into this story than I already have. As with “Kings of the Night,” my reasoning is that I simply don’t wish to spoil what comes, but I would hope what I’ve described thus far is enough to convince you that “Worms of the Earth” is a story that’s well worth your time. Indeed, it’s often lauded as one of the very best novelettes Howard ever wrote, and I fully agree with that assessment. His contribution into the Cthulhu Mythos with this story not only lends a much needed touch of recognizable history to the feeling of unknowable ancientness that Lovecraft often tried to invoke in many of his own stories, but does so in a manner that compellingly showcases how and why a figure who’s seen as noble and legendary, like Bran Mak Morn, would turn to powerful, unknown, and dangerous forces.

Fortunately, those of you interested in reading the story don’t need to look far, as I found it online while searching for reference materials for this essay. You can find it here: Worms of the Earth

On the whole, Bran Mak Morn and the Picts represent a unique facet in the literary life of Robert E. Howard. Among a plethora of characters and ideas written by a man who, by his own admission, will rarely return to a character once he feels the stories he’s drawn from them are tapped, the Picts represent a steady force that maintained staying power across his career and life. He was, as he once told Lovecraft, singularly fascinated with them, and had many plans to write stories involving these people and their legendary Last King.

Unfortunately, these ideas never saw completion before Robert E. Howard took his own life. His letters and incomplete manuscripts give us an idea of what these stories may have been like, as well as what his planned approach with them was, but we’ll never truly know what may have come of them under his hand. I found a decent variety of opinions on this matter while refamiliarizing myself with Bran Mak Morn and the Picts; from ardent supporters who loved the idea of what seemed to be a planned anthology novel that focused on the history of these peoples and their empires over specific characters, to folks who believe the idea leans too heavily into something Howard already spent too much time on in his short stories, to others who were lukewarm on the concept as a whole.

Regardless of how we may feel about what might have been, or our feelings on the various Bran Mak Morn collections that have been compiled over the decades–in my research, the trend of including almost any story focused on the Picts into collections listed as specifically being for Bran Mak Morn proved the common rule–the impact that this fictionalized race and their king had on Robert E. Howard is undeniable. From a fascination that followed him as a youth of thirteen, to a topic of regular correspondence with a friend and contemporary who found equal posthumous fame, the spirit of the Picts followed him throughout most of his life. I can’t help but imagine how else he might have engaged with this ancient people, and with Bran Mak Morn, had Howard not chosen to take his own life.

Alas, we cannot truly know. We can only read that which he gave us in his life, and wonder at the rest.

My first novella, In the Giant’s Shadow, is available for purchase! Lured to the sleepy farming community of Jötungatt by a mysterious white raven, Gaiur the Valdunite soon finds herself caught in a strange conspiracy of ritual murder and very real nightmares.

Purchase it in hardback, paperback, or digital on Amazon now:

I find myself surprised that Howard never wrote of the Amerinds in his books. He's a son of Texas, home to the Comanche and Apache.

I'm going to have to find the CMM books and read them.

Won't lie I've always struggled to get into Morn. He's the one character I find somewhat tedious to read, unlike Kane, Kull and Conan.