"What should a man do with the sword of Welleran?" - Musings on the Short Story by Lord Dunsany

I’ve become quite fond of listening to

’s podcast, The Deceneus Review, across the last few weeks. I haven’t listened to anywhere near all of them. The man just hosted his 30th episode and ended his first season at the end of last week, and the episodes seem to average out at two hours. Unfortunately, this places it in the realms of something I’d like to listen to more frequently, while also forcing it to compete with all the other wants and needs vying for my time. Books to read and write, essays to think through, (That’s why you’re here today, is it not?) projects at home which need finishing, the daily chores, and all of that on top of working six days a week. If not for the fact I get a goodly amount of downtime at work, it’d be a more profound struggle to find the time to write the stories and musings which occupied my mind across my year-and-a-half on Substack.His podcast is interesting to me for a number of reasons, not the least of which being the chance to glean fresh insights from people whom I may not agree with politically, spiritually, or philosophically. More than that, though, the conversations had on the show are simply engaging in a way that it takes active hold of my attention. Some of the guests he hosts are other writers which I follow here, and many aren’t, but all of them have brought something interesting to the table in terms of the discussions had. Thus far, every one of the six episodes I’ve listened to has managed to actively engage my mind, keeping me thinking right alongside the discussions had. This was especially welcome with the final episode of season 1, which made the continuing tedium of repainting the master bedroom in my house a breeze on Saturday.

I bring up The Deceneus Review, and its 30th episode in particular, because of a request Alexandru made near the episode’s end. I as yet have no idea why, given that the new season of his podcast has yet to begin, our good host suggested that anyone who plans to listen to the first episode of the upcoming second season (which he plans to begin sometime in December) read a particular short story. That being, “The Sword of Welleran” by Lord Dunsany, published in 1908 as the first of a collection of short stories in his third book.

I don’t know how Alexandru plans to approach the story in the premier of his second season, nor will I attempt to guess at such. What I can say is that I found the story to be fascinating, if a little challenging to read due to the older style in which it was written. It’s not extremely difficult to parse by any means, but the Lord Dunsany’s style is reflective of his day and that might necessitate the re-reading of a passage here or there to get the most out of it.

This is by no means a slight against the work in my mind, but merely a reality that must be considered. I ran into similar challenges, albeit to lesser degrees, the first time I read H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine in college, and then again earlier this year when I read The Last of the Mohicans. This hurdle has also been present in my continued reading of Musashi, but not nearly so much so as these prior works. Personally, I chalk that up to the fact that while Musashi was initially written in the 1930’s, it didn’t receive an English translation until the 70’s, and the language used in the writing of that time is far closer to what I’m used to seeing in books as an 80’s and 90’s kid.

I digress, though. My point here is to say that the challenge of reading older works is a worthwhile one, and in the case of “The Sword of Welleran,” I came away from that challenge with what I hope are some interesting observations.

Before I begin in earnest, let me first suggest that readers of this essay pick up a copy of the story to read for themselves. While it clocks in at 37 pages within the book, this is due more to the book’s formatting than actual word count. In reality this story is rather short, easily able to be read in about 20-30 minutes, or faster still if you’re used to the older style of writing Lord Dunsany uses. Additionally the book has been in the public domain for quite some time, which means it’s not difficult at all to find free versions of it available online with a quick web search. This means that even if you’d only be checking it out as a curiosity, you’ve nothing more to lose than perhaps half an hour of your time. A worthy trade, I’d say.

Now then, onto the meat of things. The first thing which stood out to me was the manner in which Lord Dunsany presents the story. I already noted the style in which he writes is recognizably of his day. The prose features many of the stylistic quirks one would expect of late 19th and early 20th century stories. However, “The Sword of Welleran” goes beyond this in the sense that there seems to be a particular deliberateness to the language Lord Dunsany uses. This could easily be me reading deeper into this than is needed, but I got the distinct sense that this story was quite intentionally written in such a way that it would read as though it were directly translated from an oral retelling.

Again, I could be reading deeper into this aspect than I should be. I’m admittedly not very familiar with Lord Dunsany’s work, so I don’t know if this is something repeated across his writings or not. It could just be a simple stylistic choice of his, but it stood out to me all the same. The deeper I got into “The Sword of Welleran,” the more I felt like I was sitting in a tent or a camp around a bonfire and listening to someone recount the tale of the inviolate city of Merimna and her legendary heroes, chief of which is, naturally, Welleran.

As a curiosity, I decided to test this for myself. About a quarter of the way into the story, I began reading passages aloud, albeit at low volume. I’m still at work after all, and it wouldn’t do to have wandering customers staring at me for that when I already get enough glazed over stares when I try to explain to them why different kinds of paint exist. Anyway, my doing this led to a small revelation: it was easier for me to digest the story reading it aloud than it was doing so in silence. The quirks of the writing which I’d been stumbling over weren’t nearly so much of a problem when read aloud, which cemented this feeling of transcribed oral tradition in my mind. (Though, again, that could just be me.)

This feeling was further enforced by the story itself. “The Sword of Welleran” opens on the glory of the city of Merimna, describing its gleaming towers, high walls, and the mountainous valley in which it sits in high detail. Similar detail is also afforded to the statues of the city’s six heroes; Welleran, Soorenard, Mommolck, Rollory, Akanax, and young Iraine; as well as the sword and cloak of Welleran which are on display in the city and treated as holy artifacts. By contrast the people within the story, and this includes any named characters, receive minimal description or characterization. Instead we’re given small snippets of their lives, with most of our time spent observing the unarmed night guardsmen who clad themselves in purple raiments and carry burning tapers as they march through the city ramparts at night, singing of Welleran and his deeds while the sentinels who keep watch during the day sleep.

The only characters we spend a significant amount of time with are Rold, a young boy at the start of the story and a young man by its end; and two desert thieves slated for execution who are sent to sneak into and spy Merimna’s defenses. These thieves come from one of the scattered desert tribes from the lands Merimna used to rule over; tribes which have reconquered their land and pined to take the city and its riches for themselves for a century. Rold, on the other hand, is a loyal and lawful child of Merimna who respects the legend of Welleran, but questions why one would need his sword not just when he’s a boy, but also as a man.

Doubtless, there are those among you who are already wondering not only why Rold would ask this question when there are enemies plotting to invade the city. Put simply, Merimna has been a city that’s only known peace since the days of Welleran and the heroic men who followed in his footsteps. These are a people that no longer know war, and they celebrate his sword, his cloak, and his deeds without a proper understanding of the cost. This is also reflected in the night guard who, as I mentioned earlier, walk the battlements unarmed.

All of the above feeds into one of the core reasons why “The Sword of Welleran” reads as if transcribed from oral tradition. The story is written like a legend of the ancient world, complete with larger-than-life heroes, a peaceful people living in an idyllic city, and barbarians outside their gates poised to take advantage of their ignorance. Only through divine intervention can Merimna be saved from the building armies of the desert robbers, and that intervention comes in the form of the spirits of Welleran and his fellow heroes.

One detail that I particularly enjoyed about this segment of the story was Lord Dunsany’s willingness to hold back in terms of what Welleran and the other five were capable of. Though present in Merimna once more, drawn there from the afterlife by the sense of impending doom reigniting their desire to protect their fair city and her people, these men are still dead. Many modern fantasy stories would likely have them appear before someone directly, Rold being the most likely candidate in this case, but Lord Dunsany rationalizes that the dead can’t interact with the living in direct ways. For as loud as they scream and cry out, the living will never hear them, thus the night guard cannot be roused to action by them.

So it is that they must engage with those closest to the realms of the dead, which means those who sleep and dream. Welleran and the other heroes set out to seek the dreaming men of Merimna and rouse them to action, leading them to arm themselves with the weapons of their forefathers which still hang in their homes, then gather outside the ravine where these heroes ultimately laid themselves to rest. Welleran, however, seeks out one to lead them with the symbols he knows will spur them to act: his cloak and his sword. Naturally, the one he chooses is Rold.

I’ll not dig much deeper into the story than I already have, because I don’t want to fully spoil the ending. Speaking of, if by this point you haven’t read it already and feel intrigued, I highly recommend doing so. That said, I do still want to discuss the ending in part, because it’s there that much of the story’s meaning comes out.

As is expected at this point, the men of Merimna clash with the oncoming armies of the desert robbers, taking the attackers by surprise as they expected a sleeping and unarmed city to be waiting for them. The rout is swift and decisive, with the robbers defeated and deflated as Rold leads the men of Merimna into battle with a cry of, “Welleran! And the sword of Welleran!”

Ultimately, it’s a fortunate day for Merimna. The invaders are turned back and the city is safe thanks to her men taking up their ancestors’ arms and defending her. However, these are a people who have only known peace in their lives, and in those moments after the battle, Rold recognizes a dark truth. For all the glories and praises they heaped upon their heroes, Welleran in particular, they had no concept of the cost of human life that came with those glories. To my mind, this is what makes “The Sword of Welleran” stand out against similar stories of its type. Where much of our fantasy and fairytales would present us with stalwart warriors, hero kings, mighty champions, and so on; Lord Dunsany shows us a young man who not only walked in the footsteps of his hero, but did so with his cloak worn and his sword wielded, and who comes away in grief at the lives taken by what he now views as a terrible weapon.

There’s a lot of fun to be had in stories of fantasy and adventure. Whether they be the better written options among more modern faire, older classics that earned their place in the annals of history, or the enduring legends of ancient civilizations, there’s a good amount of joy and entertainment to be found in them. However, there’s also a lot of romanticization, and while I’m not familiar enough with Lord Dunsany to say for certain, I do think he recognized this. I think this is why he ends “The Sword of Welleran” on the somber note he does, instead of having the men revel in their victory. It was a turn which I’ll admit I didn’t see coming, but a welcome one that carries a valuable lesson for us to keep in mind.

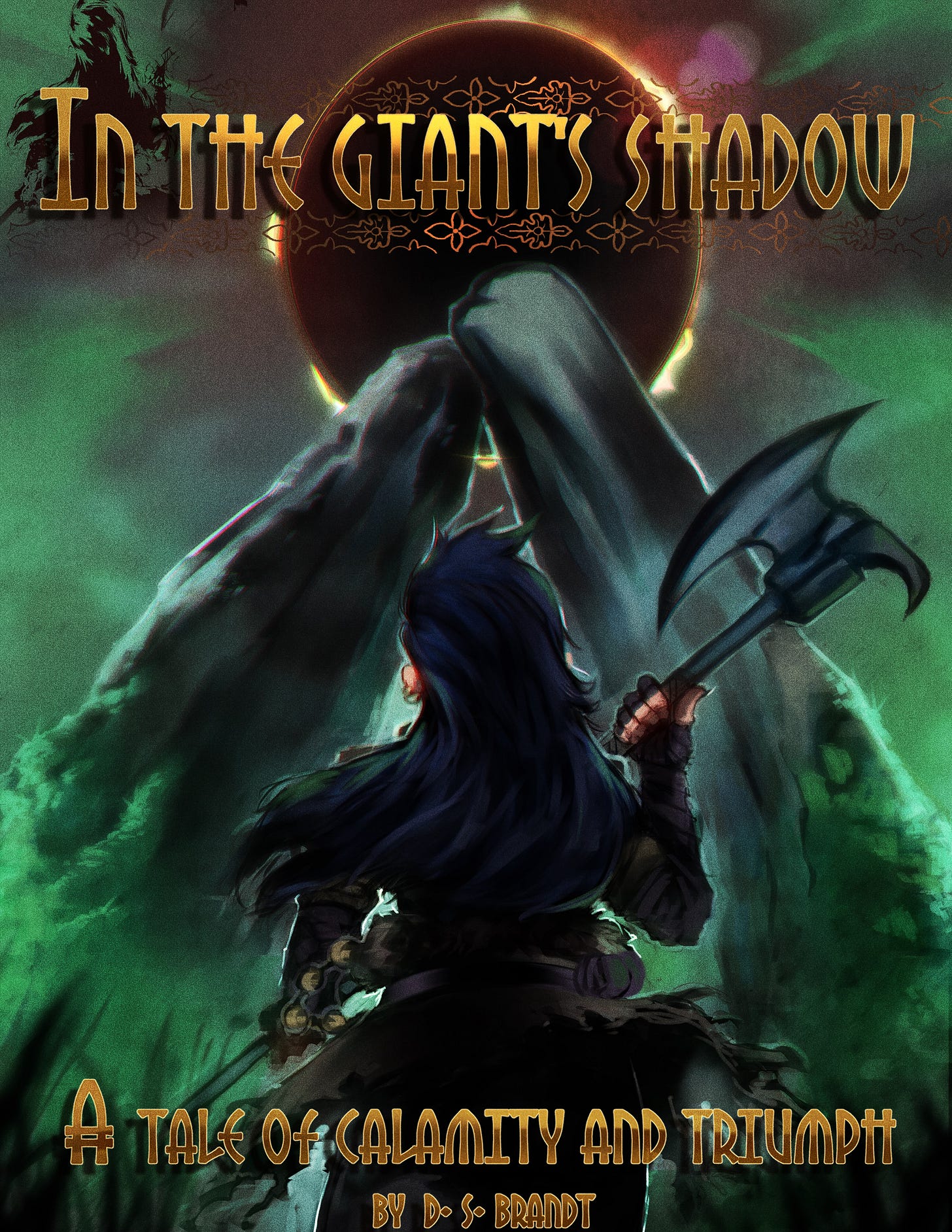

My first book, In the Giant’s Shadow, is now available for purchase in hardcover, paperback, and digital formats! A mysterious dark fantasy adventure set in a Viking age themed world, In the Giant’s Shadow follows Gaiur the Valdunite as she becomes embroiled in the machinations of a wicked force hiding away in a rural farming village. Caught up in a conspiracy of ritual murders and very real nightmares, will the young wanderer manage to uncover the secret behind the town’s ancient, monolithic gate? Will she be able to survive if she does?

Purchase the story here:

Excited to see you write about Dunsany! He has some interesting short stories that subvert what would now be traditional fantasy tropes, although ironically he was the "proto-fantasy" writer. I would also recommend his short story "the hoard of the Gibbelins" since I think it pairs with "Welleran" in the sense of not ending the way you expect (and is free to read online!). Also, great point on how his writing reads very well aloud. I'll have to try that on one of his stories sometime.

I have read "The king of Elfland's daughter," and enjoyed it. I've now downloaded "Sword of Welleran" and will read it.

I'll let you know what I think afterwards.